A woman sits in the Archive reading room, where she has managed to arrive after many interruptions connected with the details of her PhD degree program. On her table there stands a huge folder containing unbound documents of the first half of the seventeenth century coming from Venice; in particular, she is searching for handwritten newsletters, also called avvisi in Italian. Inside the folder, the documents are grouped in several pink subfolders (the colour adding an unusual spark of joy) and she starts reading the first one. After many pages read and many notes taken (in three hours of work apart from a coffee chat with another archive patron), she is finishing the first subfolder: already she has learnt which news and events were considered important and conveyed through this medium, but she hasn’t yet found any information about the writers of the avvisi. Arrived at the last document, her eyes light upon something unusual…

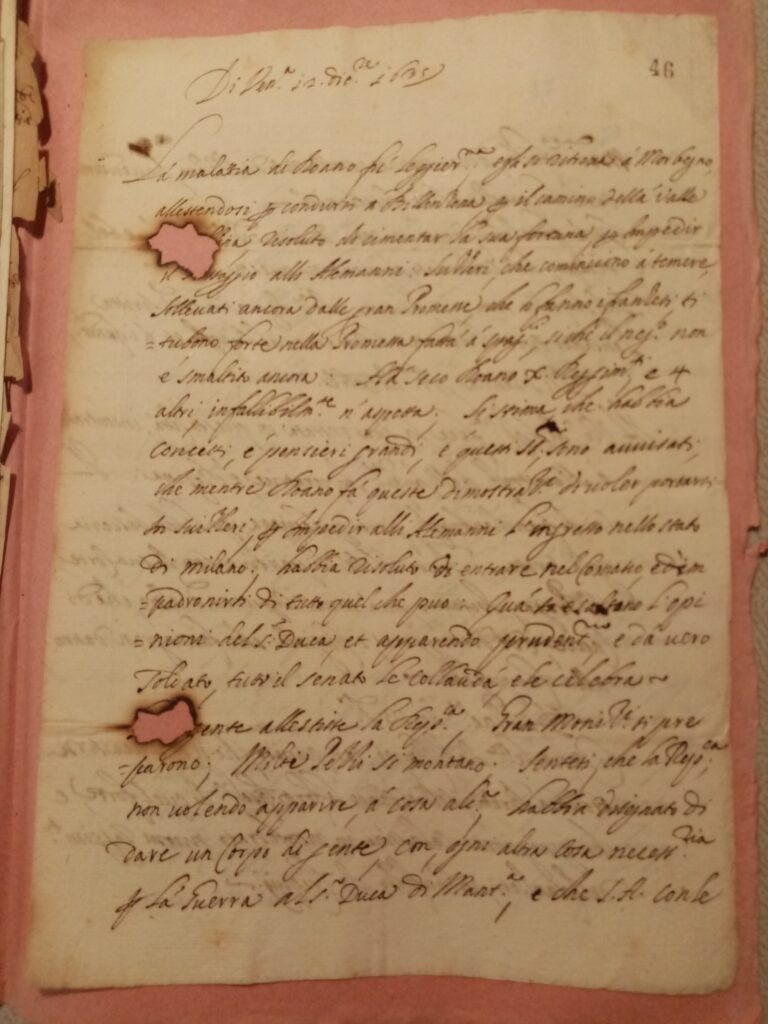

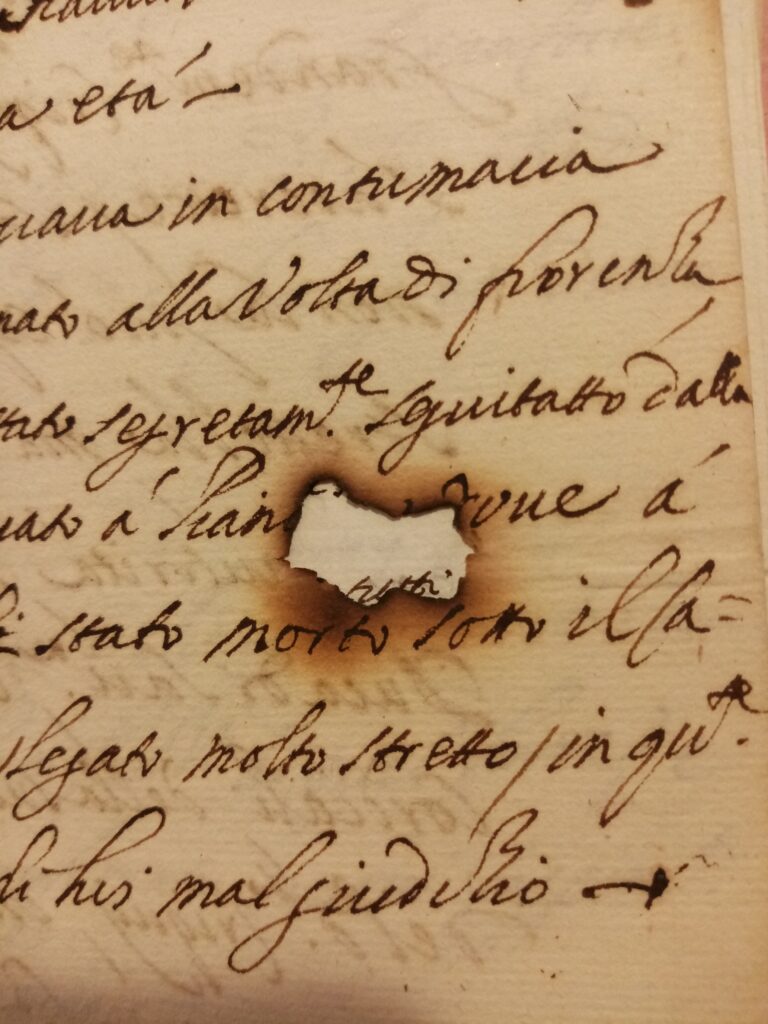

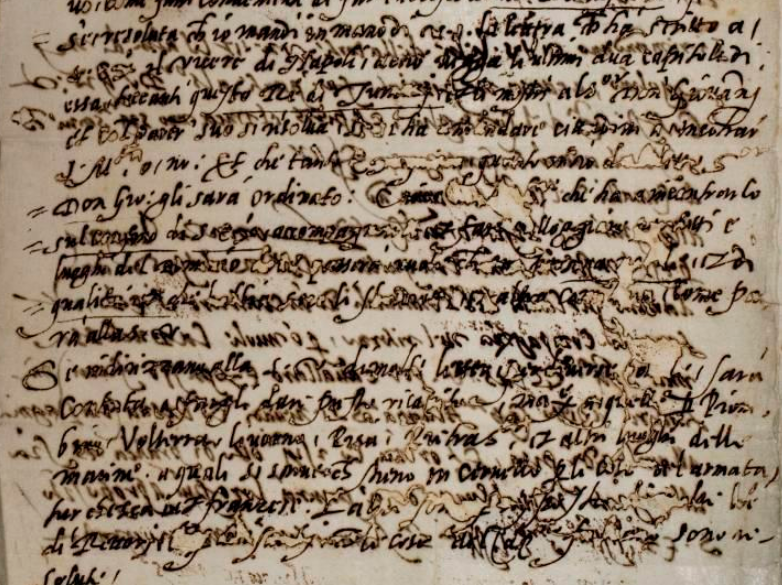

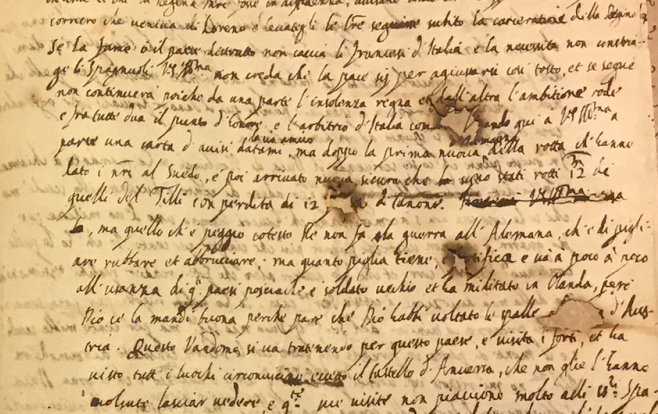

What is going on here? She wonders. Two big holes go right through the two-page newsletters. Caused by a drop of ink? She knows that iron gall inks, in certain conditions, can burn the paper. But can the ink create damage like this? She remembers drops of ink found in other documents, even earlier ones, but nothing compares to this avviso. Then, looking better at the two holes, they appear symmetrical: could the origin of both be unique and could the damage have happened when the newsletter was folded in half along the short side? It is possible, and that would explain the presence of two nearly identical holes. But what is the cause of the two holes? A burn? What if a past reader while reading the newsletter folded in half at the light of the candle, got too close to the flame and the paper caught fire! Too fanciful? Or could the holes be caused by the hot ash falling out of the reader’s pipe? But this option opens many correlated enquiries: were tobacco pipes widely diffused in Italy in 1635? Who smoked them? Could the ash technically fall from a pipe? At this point, she thinks to need a tobacco pipes’ historian to solve the question… but where can she find such an expert?

Suddenly the bell rings, the archive is closing! Time passes: for a while she can return to the reading room only with her brain… But she will be back soon enough to view the document again, for she has to find an answer!!!

What may seem like just a personal anecdote is actually another day in the material history of the avvisi. The Euronews Project is studying the content, network, diffusion, language and rhetoric of the manuscript newsletters, which, however, are first pieces of paper with ink. Understanding the writing practices of the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries is essential to getting a better grasp the newsletters’ production. Writing in the Early Modern Period was quite laborious, and many items went into the making of a handwritten text. In addition to the obvious paper and ink, the writer had to get feathers of the proper size to fashion into quills; an inkpot; sand or pounce or pin dust to sprinkle onto the manuscript in order to absorb the ink excess; a writing desk and, finally, wax, floss, string, ribbons and seals for sealing the letters to which avvisi were often attached.[1]

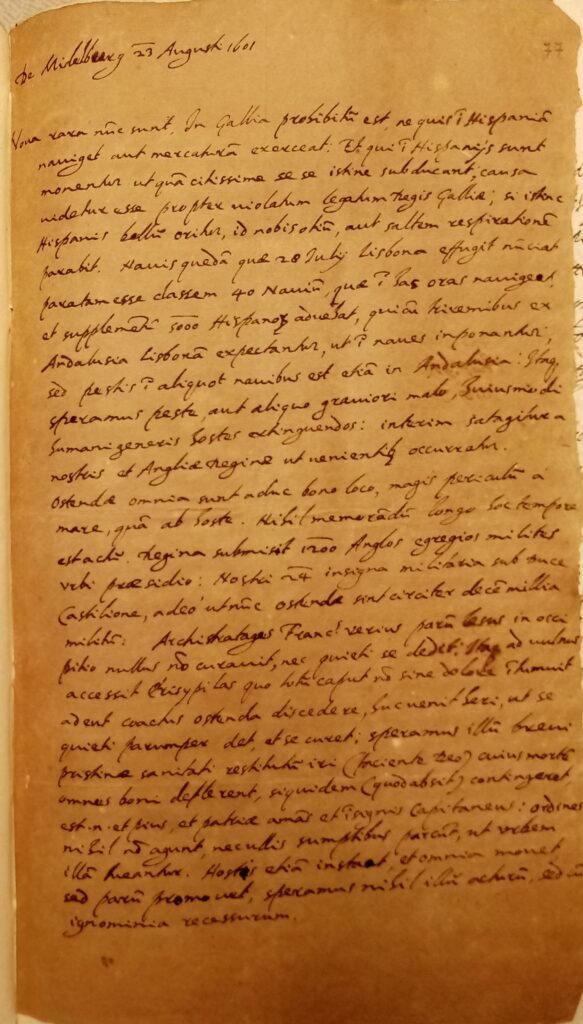

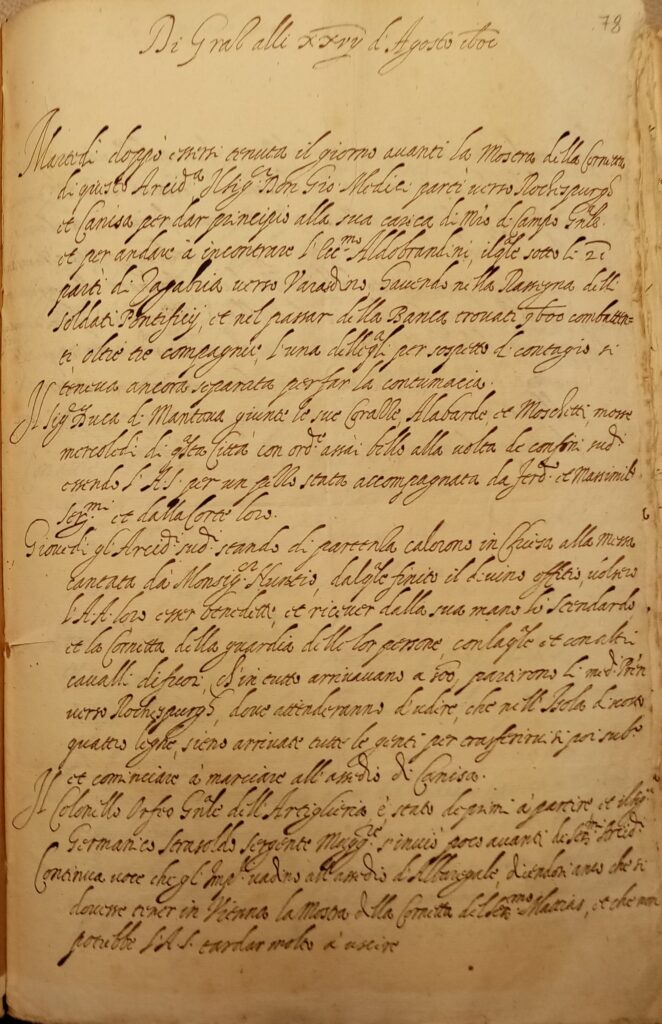

Although the writers of avvisi were mainly anonymous and often haven’t left any traces of themselves other than words, the material analysis of the paper used can give some clues. Watermarks help to date the paper and to establish its provenance, whereas colour indicates the quality of the paper.

Firenze, Archivio di Stato, Mediceo del Principato, vol. 4578, c. 77r

Firenze, Archivio di Stato, Mediceo del Principato, vol. 4578, c. 78r

Identifying all the watermarks of the 200 avvisi volumes in the Mediceo del Principato would become itself a project. However, a historian must also be able to investigate these material aspects for a more complete understanding of documents and events, particularly when it comes to media history.

Interesting evidence can also be obtained from the study of the inks used to write the avvisi. We know from a stimulating chat with Daniela Iacopino, a researcher at the Tyndal National Institute, that our inks are probably iron gall ones, known since Roman times, widely used in the Middle Ages, and standard from the Renaissance through the Nineteenth-century. Apart from their role in the history of western civilisation as vehicles for conveying part of our textual, musical and pictorial heritage, iron gall inks are also among the many threats endangering the conservation of manuscripts, documents and drawings due to their corrosive properties.[2]

In the past, they were greatly appreciated for the indelibility and hardship to remove, a feature that made them perfect for official records. Furthermore, iron gall inks, which could be produced in the household or bought from peddlers, were easy to manufacture, as many Early Modern manuscript and printed recipes attest.

Consider these instructions “To make common yncke” from the early English writing manual written by John de Beau Chesne and John Baildon and printed in 1571:

To make common yncke of vvyne take a quarte,

Tvvo ounces of gomme, let that be a parte,

Fyue ounces of Galles of copres take three

Longe standing dooth make it better to be:

If wyne ye do want, rayne water is best,

And asmuch stuffe as aboue at the least:

If yncke be to thicke put vinegre in:

For water dooth make the colour more dymme.[3]

Although many different recipes existed and historical inks varied widely in composition, three primary ingredients were always present: tannin, extracted from tree gall nuts, which contain a high concentration of this material; vitriol, an iron sulfate; and gum arabic. The components of the ink cause two different processes, the acid hydrolysis and the oxidation of cellulose, which, combined, can very seriously corrode and damage the paper.[4]

Studying avvisi ink is important for historical preservation as well as for research questions such as, did the newsletters’ writers and copyists pay attention to the ink’s quality? Could they afford good quality ink? Did subscribers complain about the ink? The more experience we accumulate, the closer we will be get to being able to decide whether strange holes and other damage to paper, like the images shown here, have been caused by the corrosion of a drop of iron gall ink or by other agents, like fire.

No doubt future collaborations with Daniela Iacopino and other experts will add further nuances to our picture of the avvisi and contribute to a better comprehension of these documents as material objects.

For the moment, just like the historian of the first paragraph’s story, we have more questions than answers, but one thing is certain: ink makes us think! So often taken for granted by historians, it is as much part of the history of the handwritten newsletters as are paper, the postal network, the text.

[1] J. Daybell, The Material Letter in Early Modern England: Manuscript Letters and the Culture and Practices of Letter-Writing, 1512–1635, Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2012, pp. 30-52.

[2] V. Conte et al., ‘Imidazolium-Based Ionic Liquids for the Efficient Treatment of Iron Gall Inked Papers’, ChemSusChem, vol. 1, 2008, pp. 921-926.

J. Kolar et al., ‘Characterisation of paper containing iron gall ink using size exclusion Chromatography’, Polymer Degradation and Stability, vol. 97, 2012, pp. 2212-2216.

J. Malesˇicˇ, ‘Evaluation of a method for treatment of iron gall ink corrosion on paper’, Cellulose, vol. 21, 2014, pp.2925-2936.

[3] J. Daybell, The Material Letter in Early Modern England, p. 38.

[4] V. Conte et al., ‘Imidazolium-Based Ionic Liquids for the Efficient Treatment of Iron Gall Inked Papers’, pp. 921-922.