By Rebeka Leite Costa and Brendan Dooley

Newsletter from Rome, 24 April, 1585: “The College of Cardinals resolved that on the 21st [of April] the mass of the Holy Spirit would be sung, where it was done by [Cardinal Alfonso] Giesualdo, and with the Proper for Easter, and consequently since the Church was lacking its head, the Cardinals dressed in crimson, and after the sermon by Monsignore Moretto, and after singing the Veni creator spiritus, in the number of [blotted out] of them they headed for the conclave in a procession.”

( Il Collegio de Cardinali si risolse che nelli 21 si cantasse la messa dello Spirito Santo dove fu fatto dal Giesualdo, et con la propria di Pasqua, et per conseguenza mancando la chiesa di Pastore, li Cardinali vestivano di Paonazzo, i quali doppo il sermone di Monsignore Moretto, et cantato il veni creator spiritus al numero de….. processionalmente si ridussero in conclave.) [Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, mss. Magl. XXIV, cod. 13]

Now, the first question to be addressed in any conclave is: who could be pope? The answer is technically any Catholic. However, while this is the truth in canonical theory, in practice it is far from reality, because it is absent from historical context. Popes were elected based on the political context of their time. And more than that, they were a kind of image of the political culture of their time.

From the time of Constantine, through the Middle Ages, there was a great hegemony of the Italian aristocracies when it came to papal power--with the exception of the Avignon period, dominated by the French. The first point to note in this scenario is that the Italian aristocracies are multiple and competing with each other. Romans, Florentines and Bolognese usually do not want the same thing and usually compete for power with each other, and one of the main games they used for measuring their power was papal “chess”. Therefore, they cannot be considered a unit in the political sense.

One thing that was indispensable for a “papabile”at this time was that he be an aristocrat, born of a good family, and, evidently, an ecclesiastic. Furthermore, there were conditions that only someone well-versed in dynastic relations could understand. It was necessary to build networks of power that would take him to the papal throne and protect him when he received the triple crown.

When talking about the Renaissance world and this moment of transition and transformation, the situation gets a little more complex. The issue is very evident in the face of the constant changes brought about by the Protestant Reformation and by so-called “Herética Germania” or by the discoveries of a “new world” by Spain and Portugal. This discovery somehow made the other countries cringe in fear because they were dealing with an exponential increase in power on the other side.

At this point, a little more context will be important. Philip II of Spain ( and I of Portugal) was the monarch who joined these two crowns. And that was just one of the reasons, plus the expansions to America that made him terrifying in front of other aristocrats and extremely dangerous for the European balance of power if Spain at that moment got a pope on its side. In this way, when Gregory XIII died, there remained a big question. Who could hold the office of pope?

For the Medici Florentines the answer was clear: it could not be the Bolognese, because as Belisario Vinta wrote in the letter below they had already “goduto il papato XIII anni” (enjoyed the papacy for 13 years) On the other hand, the Medici, even though they had a lot of power to pressure one and elect a pope, could not name one of their direct family. That is, they had reactive power, but not proactive. The attitude of the aristocratic families of the Italian peninsula was very negative to the appointment of a Medici. In this way, it seems that an impasse had been reached.

This reactive form of power of being able to demonstrate, in a very singular way, that the Medici were at the beginning of their decadence. This is because the inability to act actively in the papacy was certainly an indication of the number of enmities made over the years, which had affected his capacity for administration in the face of the complex networks of power of the “Ancien Régime Coopérative”. At the same time, it was an indication that they were still feared, this premise can be verified by observing the other face of reality: negative power. That is, the Medici had alliances that guaranteed them a kind of “veto”, in fact this is more impressive they had enough votes to assure the conclave and prevent any candidate from taking the throne of Peter without his endorsement. However, they were unable to elect one from their own household. That is, through their alliances, even if precarious, they guaranteed power.

However, there was a greater complication than the intrigue among the Italian aristocracies: the possibility of a Spanish pope. That would be the worst fate in the minds of all the aristocracies of the Italian peninsula. Therefore, they decide to make an alliance. They even conjecture about the possibility of allying with the French, and they guarantee some votes just in case, although they are not sure as a bloc whom they should support.

The phrase “Loro faranno il papa” (They will make the pope) is extremely suggestive here. In context, it means the Grand Duke will get a pope (without naming a specific candidate). But it’s very incisive about a selection that will conform to the taste of the aristocrats of the Italian peninsula, and prevent the throne of Peter from perishing at the hands of “Glorious Spain,” increasingly the dominant power in the world.

Note that there is no shame or awkwardness in saying that they (the Medici) will make the pope. The mentality of political pragmatics in relation to the papacy is extremely fascinating, and to the reader of today it may be somewhat strange. However, it must first be considered that we observe a family that had numerous popes and was influential in several other conclaves with traces until at least the 19th century. Furthermore, the relationship

between power and religion was different for these personages. The spheres, whether public-private, or religious-political, were completely inseparable. On the contrary, they were inherently symmetrical and complementary.

One question remained, however, this alliance of the Italian peninsula was for convenience, pragmatism and, above all, fear of an imbalance in the international arrangement. Therefore, it was essentially unstable. Neither party wanted to put one of the great houses in power, that was out of the question. That's why a

transitional pope seemed the most appropriate, to buy time to sign more stable agreements. In this case Felice Piergentile, who was already of a certain age and according to some reports he had not enjoyed good health since childhood, which made him an excellent candidate.

Cardinal Montalto had been a protege of Pope Pius V when he had entered the Franciscan order and had been named a cardinal by Gregory XIII. In the next part, it will be possible to observe, through the networks of power, how and why the favorable relations with two of the last popes were important for the election of Montalto.

The Conclave and the network of power

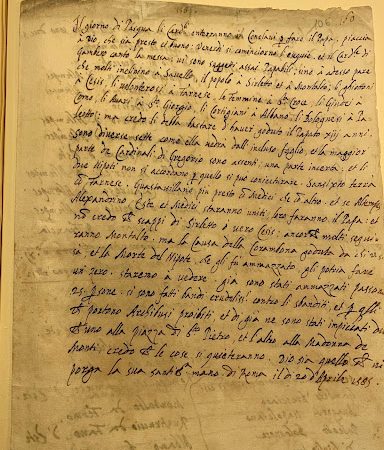

The first page of the document is shown below, containing a kind of introduction emphasizing the eminence of the conclave: this is a letter from the legato of the Grand Duke of Tuscany Ferdinando I, namely Belisario Vinta. He writes about the result of months of negotiations, and he guarantees that the result will be favorable to the Medici.

Here is the transcription:

Il giorno di Pasqua li Card.li enterranno in Conclavi per fare il Papa, piaccia i Dio che sia presto et buono: Venerdì si cominciorno li esequie. et il Card.le di Gambero cantó messa: vi sono suggetti assai Papabili; sino à adesso pare che molti inclinino à Savello[1], il popolo à Sirletto et à Montalto; li ghiottoni à Cesis, li volonterosi à Farnese, le Femmine à Sta. Croce, li Giudei à Como, li Avari à Sto. Giorgio, li Cortigiani à Albano, li Bolognesi à Paleotto: ma credo li debba bastare di haver goduto il papato XIII anni. Sono diverse sette come ella vedrà dall’incluso foglio, et la maggior parte de Cardinali di Gregorio sono assenti; una

parte incerta; et li due Nipoti non si accordo p quello si può coniecturare. San Sixto terrà con Farnese. Guastavillano più presto con Medici che con altro. Et se Altempes Alexandrino, Este et Medici stranno uniti, loro faranno il papa: et non credo che scappi di Sirletto ò vero Cesis: ancorche molti seguiranno Montalto. Ma la causa della Corambona goduta da chi V.S. sá, et la Morte del Nipote, che gli fù ammazzato, gli potria fare un zero. Staremo à vedere. Già sono stati ammazzati passono 25 persone. Si sono fatti bandi crudelissimi contri li sbanditi, et per quelli 25 portono Archibusi proibiti, et di già ne sono stati impiccati due che uno allla pizza di Sto. Pietro, et l’altro alla Madonna di Monti, credo che le cose si quieteranno. Dio sia quello che vi porga la sua santissima mano. Di Roma. Il 20 d’aplile 1585

Author: Belisario Vinta

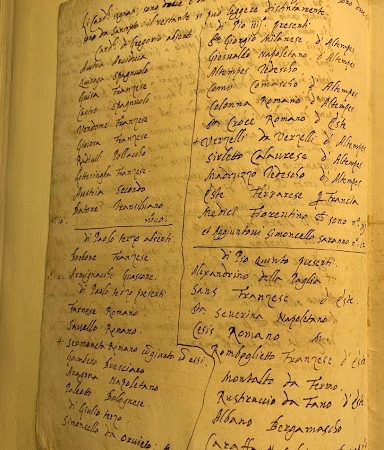

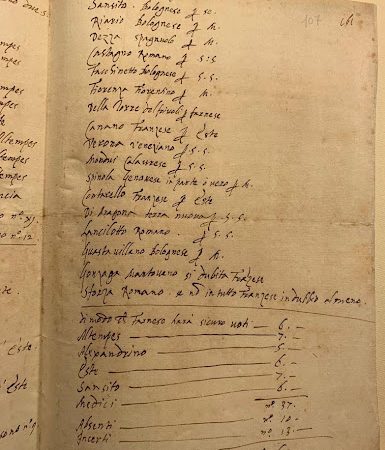

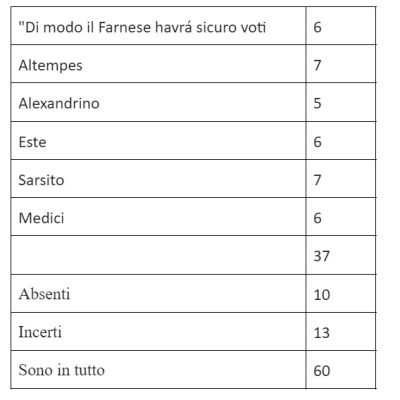

On subsequent pages we find the vote count. The votes are organized by the popes who nominated the cardinals who voted in the conclave of 1585.

Here is the transcript of the last table:

Power network

Considering the evidence, therefore, the question remains how the Medici managed to forge the alliances and why, with the result that Felice Piergentile, Cardinal Montalto, would have been elected.

Elaborating on this:

Some theoretical and methodological issues must be presented from the outset, as they can decisively influence the interpretation. As a starting point, it should be considered that the letters have at least two dense layers of parallel interests that run through them. Which was not the objective of this analysis, since doing a discourse analysis would be outside the scope of the proposed objective for this research, however it is important that the reader knows that there are such methodological problems that would have to be addressed, because otherwise they may condition historical interpretation.

The first layer of interest that is running through the documentation comes from its author. The Grand Duke's legate had a pragmatic interest in overestimating his work as an emissary, and demonstrating that his involvement had been decisive in the outcome of the conclave. Whether for the mere maintenance of their power or the ambition to expand their network of power.

The other layer of interest that can condition the interpretation is one that is a little more subtle, and therefore much more dangerous in the sense of rhetorical artifice. It relates to the sender's and receiver's communications. Both had the idea that the Medici were a political force. It was the expression of political culture, which doesn't matter whether it started with the practice or the idea. What is relevant is that it became an extremely decisive force and that the dialectic between practice and idea shaped the reality we know from the Florentine Renaissance.

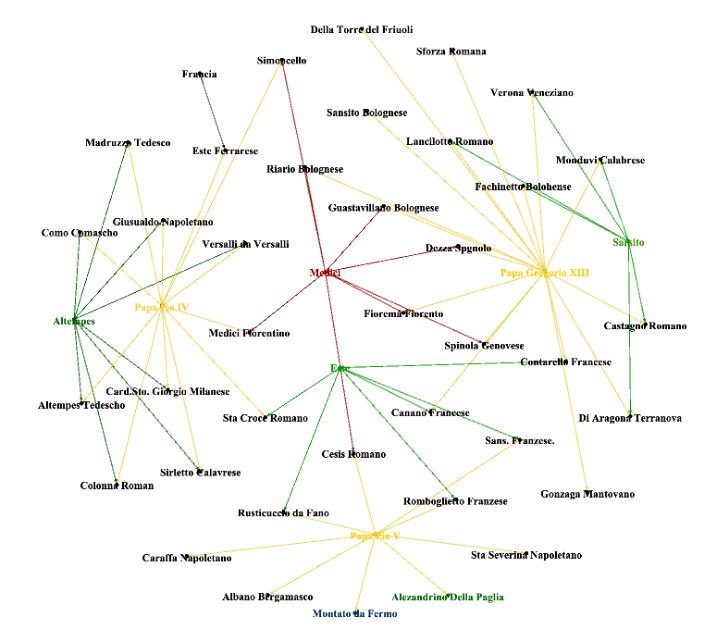

Thus, it is not surprising that diagram 2 represents a centrality of the Medici in the decision-making process. Whether for the first or the second reason, the point is that so far there is not enough data from the State Archive to demonstrate how 39% of the votes behaved, since it is known that the total count was 37 in favor of the interests of the Medici of a total of 60 gifts, which means that the Medici had around 61% of the votes in that election and 39% against it. For, as said in this letter, it was made by a Florentine legate and we should not be surprised if he had used rhetorical devices to impress the Duke.

Consider these points and proceed with the method initially proposed and the interpretation of the network, with the caution of Decastes. What can be done in this case is to contract the data of the letter with the historical context to attest to its verisimilitude. In this case, we will not do it with all the content, only with what refers to the power network itself.

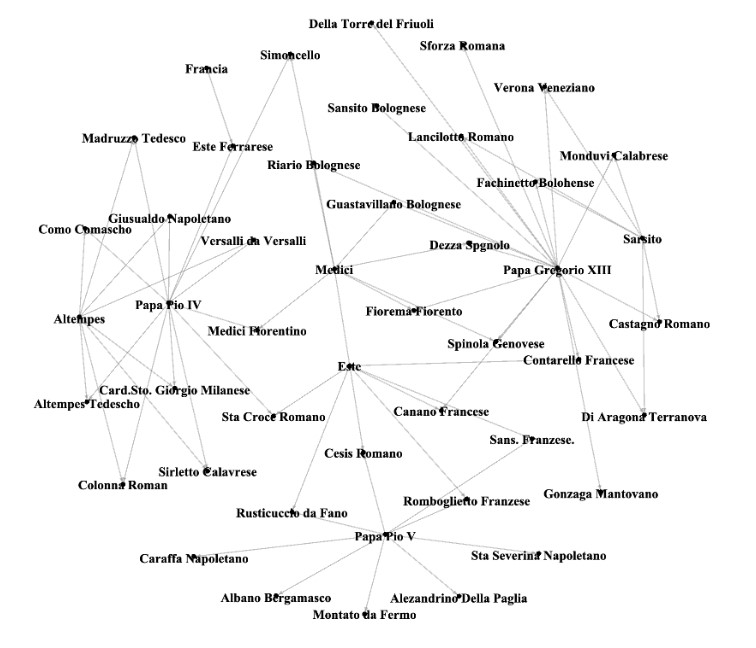

From the networks between his two great phenomena can be considered: The first is that there is a link between the pope who the cardinals were appointed and the first. The second is the strong Medici link (in wine) that acts as a kind of network vortex.

In the first one it is observed that the cardinals of Pius IV devoted themselves in Atempes, almost unanimously. While those of Gregory XIII would overwhelmingly vote for Sarsito. While those of Pius V were divided between Alexandrino, Este and Montalto.

Two reasons are theorized for this tendency of cardinals appointed by the popes to vote for the same names. The most obvious would be that a pope appoints cardinals according to his mute vision, ideals, and above all, as a result of his network of influence. The second theory - that would be valid to explain above all the tendency of Pius IV- is the generational theory, while the same generation tends to share the same traumas and worldview, considering such a restricted group that went through the same intellectual and identity formation (as a clergy) is reasonable to believe that they shared the same space of experience, so they envisioned the same horizon of expectation.

Finally, note in the diagram that Medice are not eligible, but are clearly like - a kind of vortex - being the axis that connects several alliances. And it was in this scheme that resided his power. The question remains, however, would this be the source of its power or would it be manipulation of the Legacy's information. Probably both, since both being the axis and manipulating information are sources of power.

Final considerations

In this way, the reflection on the importance and power of the papal network, in the case of Sixtus V, shows an important conclusion. It is based on the various power networks that support it, but this is not a direct relationship, as the Legacy sentence indicated "Loro faranno il papa". It was necessary to negotiate power before, during and after the council. Other documents demonstrate that in reality the power of the Pope was a great dialectic, between the aristocratic families that put him in power and later the trans-dimensional power that the Petrine throne granted to its recipient.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Betten, F. S. (1933). PASTOR-KERR, The History of the Popes from the Close of the Middle Ages (Book Review). Catholic Historical Review, 19, 203.

HESPANHA, António Manuel, As vésperas do leviathan: instituições e poder político: Portugal, séc. XVII. Livraria Almedina, 1994.

Vergangene Zukunft. Zur Semantik geschichtlicher Zeiten. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1979.

von Hübner, J. A. (1870). Sixte-Quint: d'aprés des correspondances diplomatiques inédites tirées des archives d'état, du Vatican, de Simancas, Venise, Paris, Vienne et Florence (Vol. 2). Franck.