by Brendan Dooley

Clearly, The internationalization of news in the sixteenth and seveneenth centuries not only made for more interesting reading and listening; it also profoundly affected the lives of people wherever such news was available.

Indeed one measure of the importance of translation in the news of this period might be the veritable stories of failed or null translation carried in the news, and what happens as a result.

A remarkably emblematic story that occurs in our period, reported by Giovanni Sagredo, the Venetian resident in London in 1657.

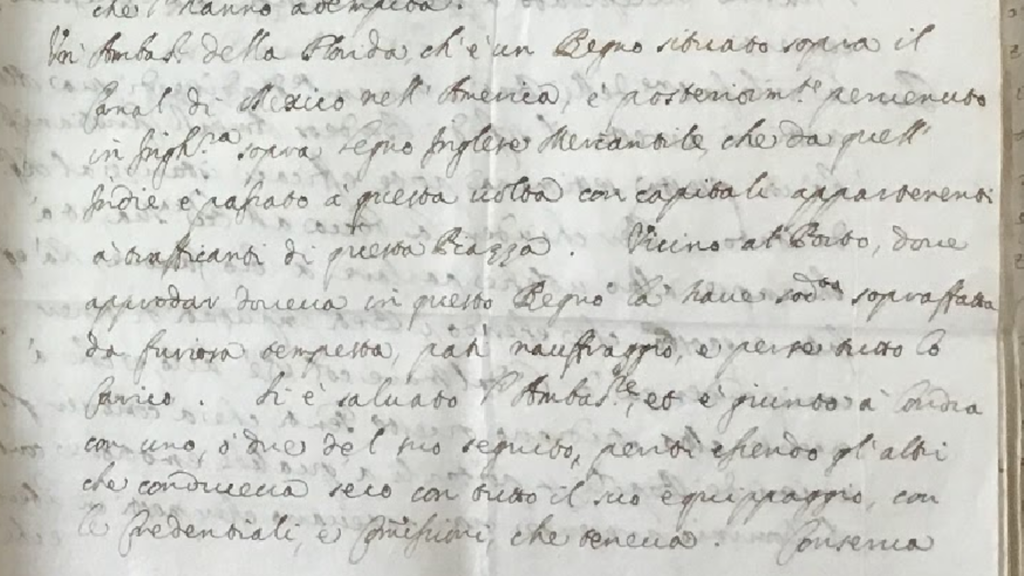

(Venice: Archivio di Stato, Senato Dispacci 48, fol. 258)

The document where Sagredo gives his report, located in the Venetian State Archives, states:

“An ambassador from Florida, which is a kingdom located on the Mexico Canal in America, recently arrived in England on English mercantile ships, which went from those Indies with money belonging to merchants from this area. Near the port, where the aforementioned ship was supposed to land in this Kingdom, overwhelmed by a furious storm, it suffered a shipwreck and lost all its cargo. The Ambassador was saved and arrived in London with one or two of his retinue, the others who he was taking with him along with all his crew and the credentials and commissions he held having perished. He keeps some other paper with him, but there is no one who has the ability to understand it, and his Interpreter having drowned, he will have no way of explaining himself to manage his negotiations.”

The disappearance of the translators casts a dark shadow over a whole episode and a whole part of the world–indicating [so the Venetian resident seems to imply] the crucial importance of having not only witnesses and informers but having translators ready to render their words.

The document goes on to say, the incomprehensible representative of the Indios “is the brother of the King of Florida himself, and he comes to point out to [England’s Lord Protector oliver] Cromuel the ease of any undertaking in that part against the Spaniards, promising in any case the assistance and encouragement of his Lord, who has no aversion or mortal enmity.” Here we have a great example of Transediting– how did the Venetian Ambassador know what the Indios’ representative was up to if there was no translator?

In any case, we are thrust into the global side of global warfare in the period– keeping in mind that Cromwell did have a reputation, in warfare, of getting the indigenous people out of the way to make room for the English settlers–at least in Ireland–so the king of Florida might not know exactly what he’s getting in to.

The report gives more details,

“He came to England completely naked, in accordance with the customs of his country, but the rigors of this climate so different from his native one forced him to take clothes and cover himself very well.” So apparently he survived.

But clearly we are also deeply into Michel de Montaigne territory here, whose essay on cannibals of a century before, was a landmark in intercultural understanding as well as translation.

Foreign news reporting in the early modern period (and maybe always) is most often motivated, chosen and fashioned according to the local politics of the places that pick it up

Between the source culture and the target culture (if we can stretch the meaning of these TS terms) much Communication may be a dialogue of the deaf (as we say in italian, a dialogo tra sordi)

However, within a modern world system soon to become global, possible avenues are eventually forged within the interstices of the media ecology, making possible real knowledge transfer as well as emancipation from ignorance if only the means and methods might occasionally be seconded by desire.