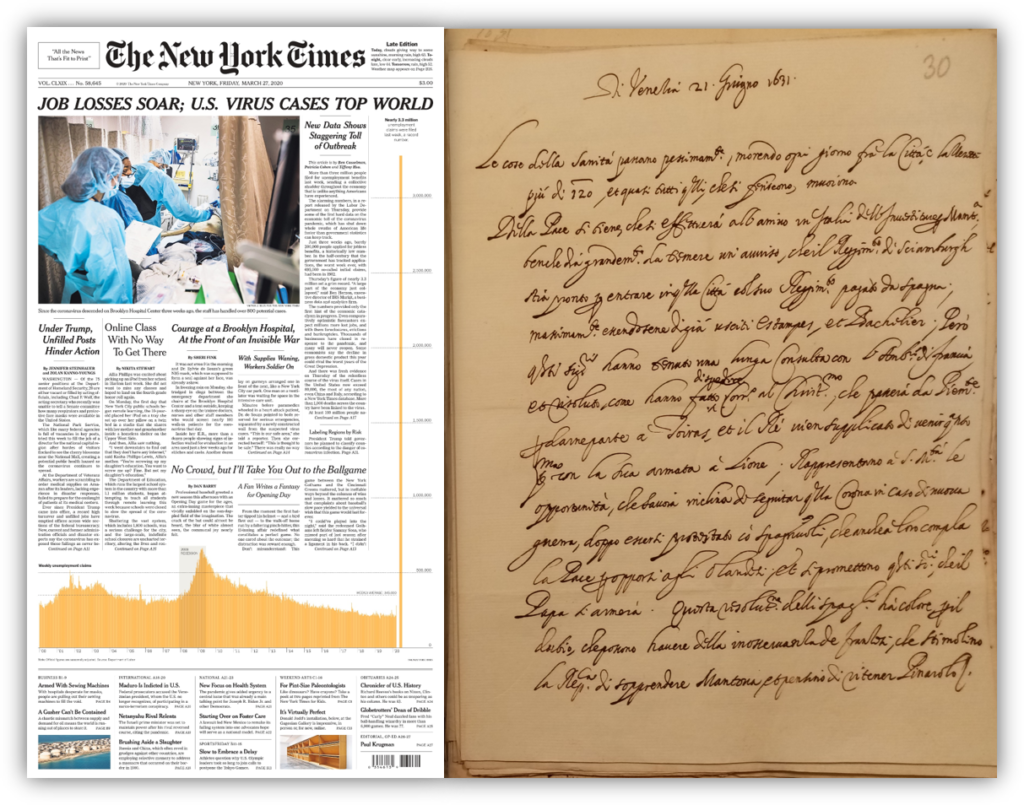

The difference between these two images is obvious, but it isn’t as substantial as we might think. On the left, there is the New York Times front page of the 27th of March, with a photo, a half page-wide graph and words to which we are sadly becoming accustomed; on the right side we see a manuscript newsletter, written in Venice on the 21st of June 1631, amidst the Italian Plague, one of the most devastating epidemics of that period. The first piece of news regards ‘le cose della sanità’, literally ‘health care matters’, and informs about the everyday casualties in the city and in hospitals. The thirst for news and the human fear conveyed by these texts is probably the same today as in the Seventeenth century. What changes is how the news travels and spreads: if now we imagine the news as immaterial, traveling virtually through the Internet, and before that through the television, the radio, the telegraph, the news was also, and perhaps primarily, an object because it needed to be materially conveyed on a piece of paper, and physically handed by a courier to another, from a place to another.

This post aims to detect what the newsletters reveal about their own materiality and how the materiality influenced their trade, network and reception. Avvisi have been rediscovered and widely studied in the last two decades by historians who, however, have mainly considered them only as textual repositories of information. But it is important not to miss their materiality, which is often linked to their content.

In early modernity, the news network was very articulated and dense, and we have evidence of that thanks to the huge number of avvisi kept in the European archives and because often the same news can be found, word by word, in two or more different newsletters, compiled in different cities. But the same way that the news items circulated around Europe, the sheets of paper bearing them travelled as well.

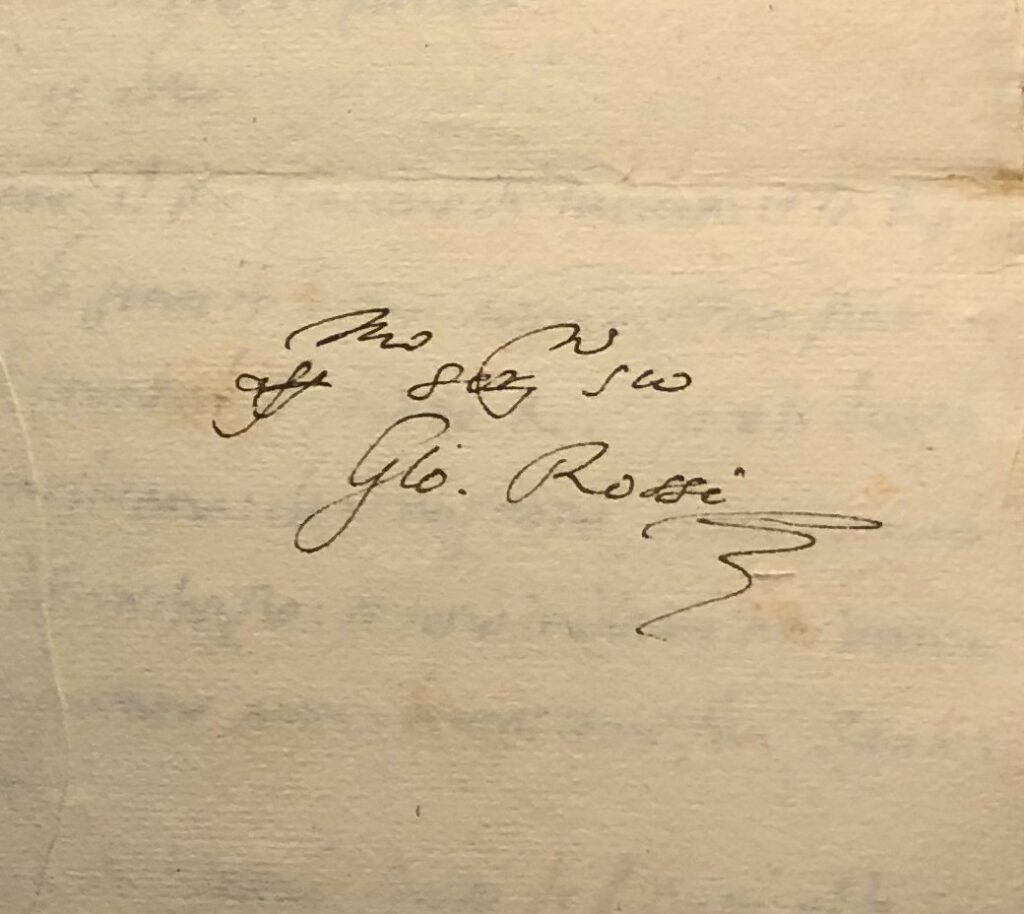

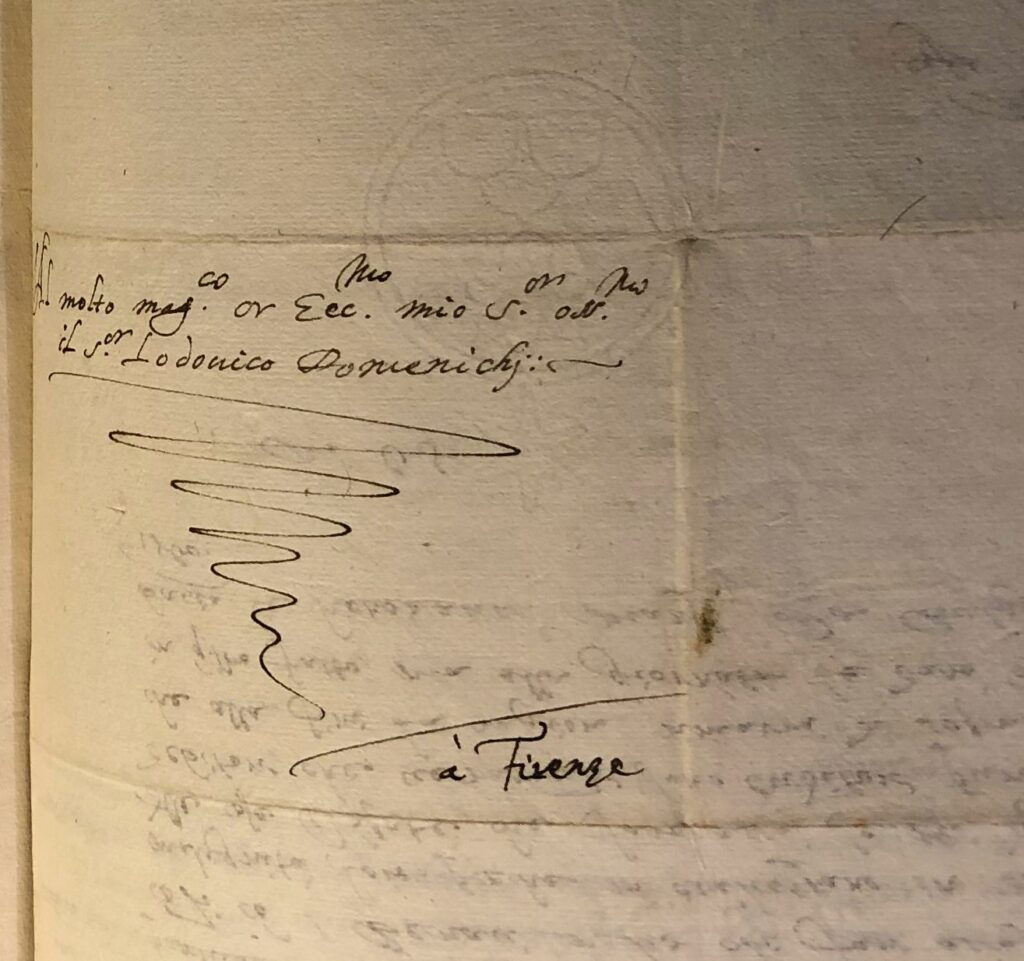

Sometimes, remembering that the newsletters travelled from a place to another, like letters, is crucial to a better understanding: on the verso of an avviso sent in 1560 by Giovanni Rossi, printer and bookseller in Bologna, we read the recipient who, surprisingly, is not the Duke of Florence or his secretary (even if the sheet is today kept in the Medici’s Archive and so, it was received by the Duke somehow), but Lodovico Domenichi, a humanist and translator. This apparently little detail, invisible if one had stopped to read the mere text of the newsletter, opens a new research path on the Medici’s network of informers and the link between bookshops and workshops providing avvisi.

Often the newsletters received by the Medici were sent by their ambassadors, residents, agents, as attachments to letters. Unfortunately, during the reorganisation of the Medici archives in the Eighteenth-century, letters and newsletters had been detached and bound in different volumes. The loss of this material and historical relationship can heavily compromise the interpretation of the avvisi’s content. For instance, the report regarding the ship Colomba, written in a newsletter from Venice, could be believed to be true, until we find the letter to which it was attached, which reads:

Your Highness will read the other news in the summaries, which bring little truth because the whole report on the ship Colomba is to be considered a lie

Virtually reconstructing the link between letters and newsletters, when possible, helps to better understand this documentary source and reconstruct historical accuracy.

Moving on to the newsletters’ content, very often the text itself is evidence of missing materiality and orality, opening a fascinating window into the news transmission process and how the news arrived at the ears and eyes of the compiler of avvisi. He could have directly witnessed the event –for instance, the arrival of a ship if he lives in Venice– but he could also have heard someone speaking in a nobleman’s house or while walking in the main city square, or he could have received letters from other informers.

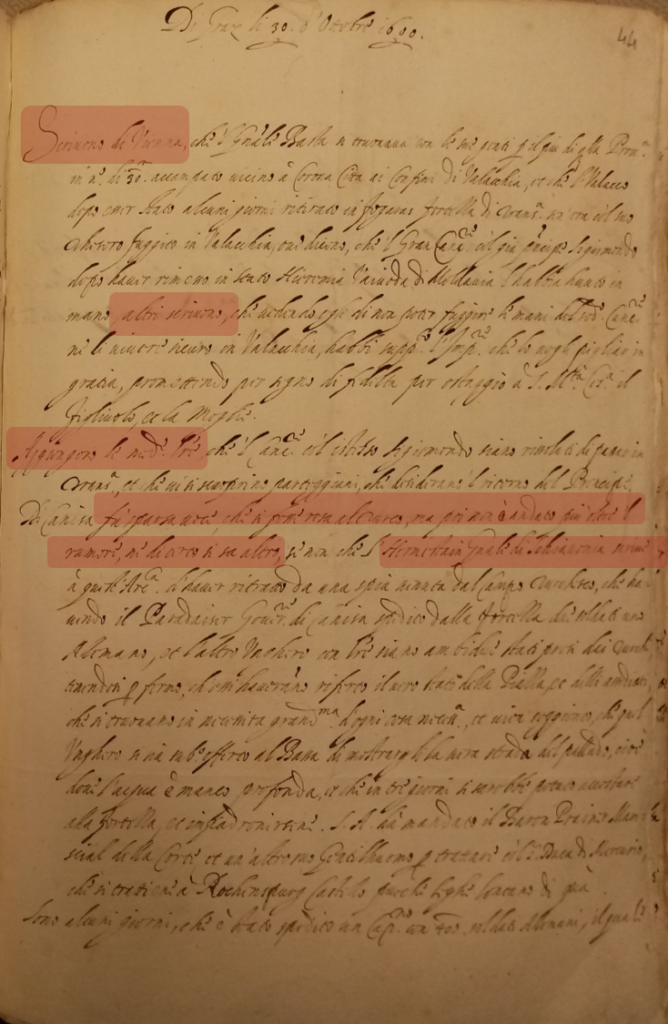

In this newsletter from Graz, the compiler wrote relying on more than one letter that he had received from Vienna as we can infer from the sentence “they wrote from Vienna that…” and “Others wrote that…”. But he also reported a rumour, spreading within the Hungarian city of Kanizsa, about which somebody had heard and informed him.

They wrote from Vienna that General [Giorgio] Basta was encamped with his people, mainly from that province and in the number of 30 thousand, near Corona, a city on the Walachian border […]

Others wrote that he [Michael the Brave], not being able to escape from the Grand Chancellor or live safely in Walachia, begged the Emperor to grant him a pardon […]

The same letters add that the Grand Chancellor and Sigismund Báthory decided to move to Transylvania […]

From Canisa [today Nagykanizsa in Hungary] a rumour about the surrender to the Ottoman Empire spread, but it remained a rumour, and nothing else was known for sure, except that Hermestain, General of Schiavonia [Slavonija], wrote to this Archduke that he had heard from a spy coming from the Ottoman camp that […]

So, behind a written page like this, there is a complex interweaving of letters and documents, that, although not materially existing anymore, can be brought to light through indirect sources. Moreover, this interweaving doesn’t appear visually through the page layout or the handwriting, but can be only detected and appreciated reading the text.

Sometimes the newsletters report incidents that delayed or stopped their journey, giving a glimpse of how much the materiality of these sheets of paper mattered in the diffusion of the news. Some documents narrate about couriers fallen in rivers with their post-bags whose documents, if retrieved, became illegible due to the ink dissolving. In other cases, the interference with the mail delivery was a political tactic. In 1571 news from Paris warned that the courier of London directed to Paris had been robbed and his mail had been brought to the English court by order of Queen Elizabeth the First.

But the biggest obstacle to the supply of news was the suspicion of plague and the fear of contagion. Letters and newsletters reached their destinations with more difficulty during the epidemics than in wartime, because couriers coming from plague-infested places were forbidden to enter into the safe cities or to pass through some regions. The newsletters were believed to be vectors of infection just like any other physical object and rules were introduced to reduce the contagion caused by them. An avviso from Venice, written in 1564, warned that the letters from Lyon should no longer be tied with twine, because of an outbreak of plague there: the avviso doesn’t say more, but we can infer that twine was believed to convey the disease.

Some years later, in 1579, a different solution for the infected mail was adopted in Rome, as this avviso attests:

On Monday, the Consistory discussed vastly the plague problem and ordered guards at the gates […]

On Sunday, due to the discovery of this letter and other ones from the post of Milan, a courier of Milan and some agents of Tassis [the master of the post] were imprisoned, and now the packets of letters, before being distributed, have to be opened in front of the commissioner of the Apostolic Chamber and other officials, as happened yesterday with the post from Venice.

And it seems that the solution has been found, that all the letters have to be collected in a house outside Rome: those that come from places suspected of plague have to be burned; the others can be sent inside the city after being perfumed, without permitting the couriers to enter.

Stopped at the city gates, the couriers were not only seen as carriers of the infection, but became metaphors of the plague itself, nearly shifting from the materiality to a symbolic level.

Often Florentine ambassadors and residents complained that they hadn’t received news about the plague because of it. The cessation or delays of the flow of news became news themselves, as this avviso written in Venice during the 1630-1631 Italian plague shows:

For the present suspect of infection, we don’t receive the newsletters from Piedmont with the speed that we would like and that would be necessary under these circumstances.

Delays in the arrival of news could also be caused by unknown reasons. However, the Florentine ambassadors and agents had to notify the Duke of Tuscany when the news arrived, but even more when it did not, and they had to be ready to collect information even in the middle of the night. For instance, the Florentine agent in Venice, Cosimo Bartoli, added this postscript at the end of his letter, at one o’clock in the morning:

I had already closed the bunch of letters, when I received the news that the signori had received letters of the first of this month from Constantinople, from which they were informed that […]

Venice, the 26th of July 1567, at one o’clock in the morning.

In conclusion, the handwritten newsletters give us many examples of their materiality and testify how much they were not considered only as text by the contemporaries, as the historians tend to do today. Taking into account the materiality of these documents furthers the understanding of their content and historical function.

This blog post gathers part of my talk given during the Virtual Symposium “On the Materiality and the Virtual”, organised by the Medieval and Renaissance Graduate Interdisciplinary Network (New York University) and held online on the 1st May 2020.