By Brendan Dooley

“Vivo sol di speranza, non potendo mirar mio vivo sole.” [I live only by hope, not being able to see my bright sun]

A cry of pain? Surely, a somewhat strange phrase to find on the back of a page in this special section of the Florentine State Archive, known as Cifrari, devoted to methods of encoding used in certain circumstances to hide the contents of particularly sensitive communications of the sort that were not supposed to show up in the public handwritten newsletters, but which the same writers used regularly.

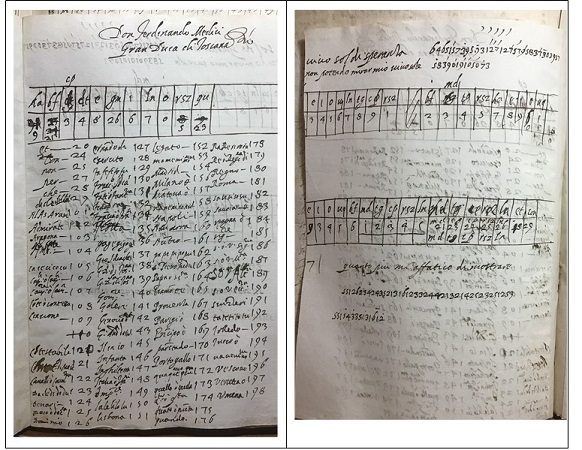

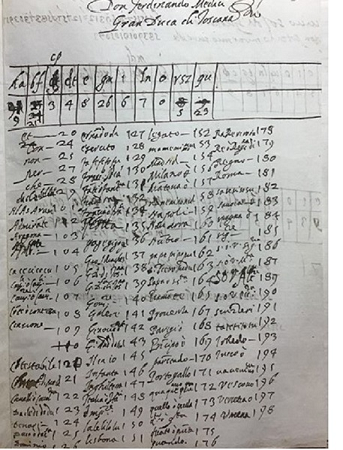

The front side of the page is headed with a familiar name, “Don Ferdinando Medici Gran Duca di Toscana”, written with a curly flourish at the end. Did the Grand Duke compile the verses on the reverse, which seem to be a “centone” or pastiche of lines drawn from different sources, the first half from Petrarch’s Sonnet CCXXVI, the second from Alessandro Striggio’s madrigal “Dolci labbra amorose”?

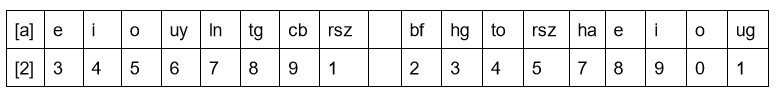

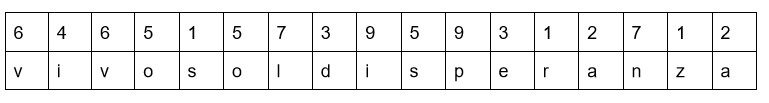

Under Ferdinando’s name we find the typical contents familiar in this part of the Archive, featuring a numerical code representing letters of the alphabet and brief expressions. On the verso, we find our centone, and next to it, a series of numbers (64651573959312712), all followed by the table below, somewhat like the one on the front side. As part of the page is cut off, we have to infer what was on the far left. A “2” standing for the letter “a”?

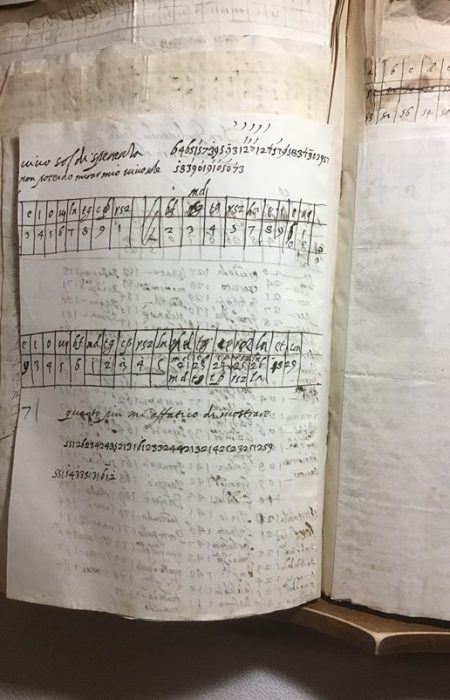

Now, carefully scrutinizing the numbers in the series next to the centone and comparing them to what is written in the table, accepting our hypothesis about the letter “a”, we can make out the words in the centone. They are the same! For instance, if we look at the first four words (without worrying about spaces) we get

Apparently Ferdinando liked the trick so much that he then tried it with another phrase, “quanto più m’affatico di dimostrare” [the more I try to demonstrate], for which he devised a somewhat more intricate code, including more letter combinations and numbers with two digits.

We see that the “a” again is missing (which we judge by context should be “1”); so “quanto” resolves as 55=qu, 1=a, 26=n, 23=t, o=4.

Fun and games? or was Ferdinando trying to say something with this test of codes? Who was his VIVO SOLE? What was he trying to DEMONSTRATE? An we imagine that such choices of expression are merely random?

Back on the first page we get a sense of the projects he may have been working on at the time, by looking at the persons and things for which a code is given, for purposes of correspondence with his staff, a line of inquiry we will be using more extensively later on:

Aragona

Ambasciatore

Contestabile

Galere

Genovesi

G[iovanni] And[rea] Doria

Italia o Italiani

Napoli

Navarra

d. Pietro Medici

Portogallo

Papa o Sua Santità

s[ua] o v[ostra] Signoria

s[ua] o v[ostra] Maestà

Toledo

Turco

Venetia

Umena

103

104

141

141

142

143

148

159

160

163

171

164

186

187

193

194

197

198

There are also decoys to frustrate the decipherer: “cacecicocu 105”, “fafefifofu 125” and the like. We are not fooled. At least we have a terminus ad quem, since Don Pietro de’ Medici died in 1604! To a future post we leave our more precise deductions about the time frame of this key!

Thanks to Neil Harris for poetic references.

FURTHER READING

Katherine Ellison and Susan M. Kim, eds., A Material History of Medieval and Early Modern Ciphers: Cryptography and the History of Literacy (Abingdon: Routledge, 2018)