By Antonello Mori

Civil wars made great news in the Early Modern period. The EURONEWS project is currently at work on newsletters and dispatches from Amerigo Salvetti and Giovanni Salvetti Antelminelli to the Florentine Court during the time of the English Civil War and the aftermath. How to convey the main issues to a wider audience?

Public history makes historical content comprehensible not only for the academic world, but above all for the general public, and increasingly user-friendly and inexpensive technologies provide many ways of achieving this goal. In the case reported here, I tried to create an effective synthesis between the academic and public worlds, between the analog and digital worlds, between past and present. Starting from the analysis of a specific historical event, in this case the so-called ‘First English Civil War (1642-1646)’[1] , the aim was to create a storytelling experience supported by digital animation techniques that could involve and inform a non-expert audience and at the same time enhance the unpublished documentation consulted.

The unpublished documentation cited, which forms the foundation of the entire work, comes from the correspondence exchanged between the Grand Duchy of Tuscany and the Florentine resident in London, Amerigo Salvetti, and covers the years between 1640 and 1646. This correspondence, held at the State Archives in Florence, has been digitised and made available by the Euronews Project in collaboration with the Medici Archive project.

To feature some of the basic ideas in a lively and entertaining way I have provided an animated video linking concepts, images and sounds.[2] Easily accessible technological resources were used for the production.

Having chosen the medium I set the following parameters of reference for the design phase:

1. First of all, the video had to be simple without becoming trivial, so it was essential to use a language that was accessible to a general audience, capable of conveying a message not only with words but also with images. The choice of our target audience, children, was fundamental, because if they could learn something from what we were proposing, everyone would be able to do so.

2. Immediacy: the main showcases in which the video is shown are the dedicated website and Youtube; therefore, I wanted to create a product that could be on par with those videos that are broadcast on a loop in an exhibition, so shortness and the possibility of viewing it from anywhere had to be fundamental. By making the video short, not only it is possible to make the most of the subject's attention without boring them, but it also allows those who interface with the video that has already started to be able to wait for it to be repeated in order to catch up on the lost parts. In a public place these are the elements that we consider fundamental for a good user experience.

3. Reliability: simplifying does not mean trivialising the contents. My background as a historian privileged the values of meticulous research and clarity regarding the sources used[3]. Although short, the text has been revised and reliable sources have been used in order to provide a contribution that, although it may appear simple, hides solid research behind it. In fact, the work began reading again all the documentation taken into account and then combine it with a meticulous bibliographic research, looking for elements that could be in line with the chosen style of narration.

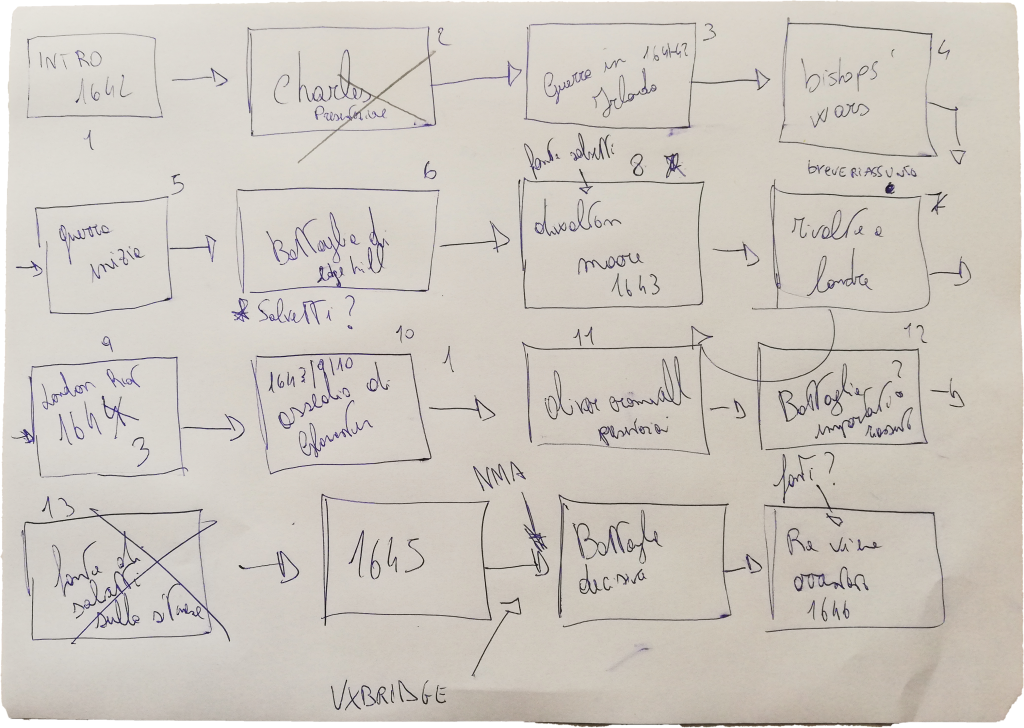

After having checked that the product met the requirements described above, a storyboard was created to determine how many animated scenes and characters should be drawn. Unlike almost all the phases of the work undertaken, the storyboard was not created digitally, but simply using an A3 sheet of paper and a pen, as can be seen in fig. 1.

Figure 1. Storyboard made for the video.

This image testifies a non-linear process, which is very different from the final product, as corrections, additions and removals were made during the course of the work, some even during editing, when it was realised that some elements might appear boring or unnecessary for the narrative, but also scenes that were too difficult to animate.

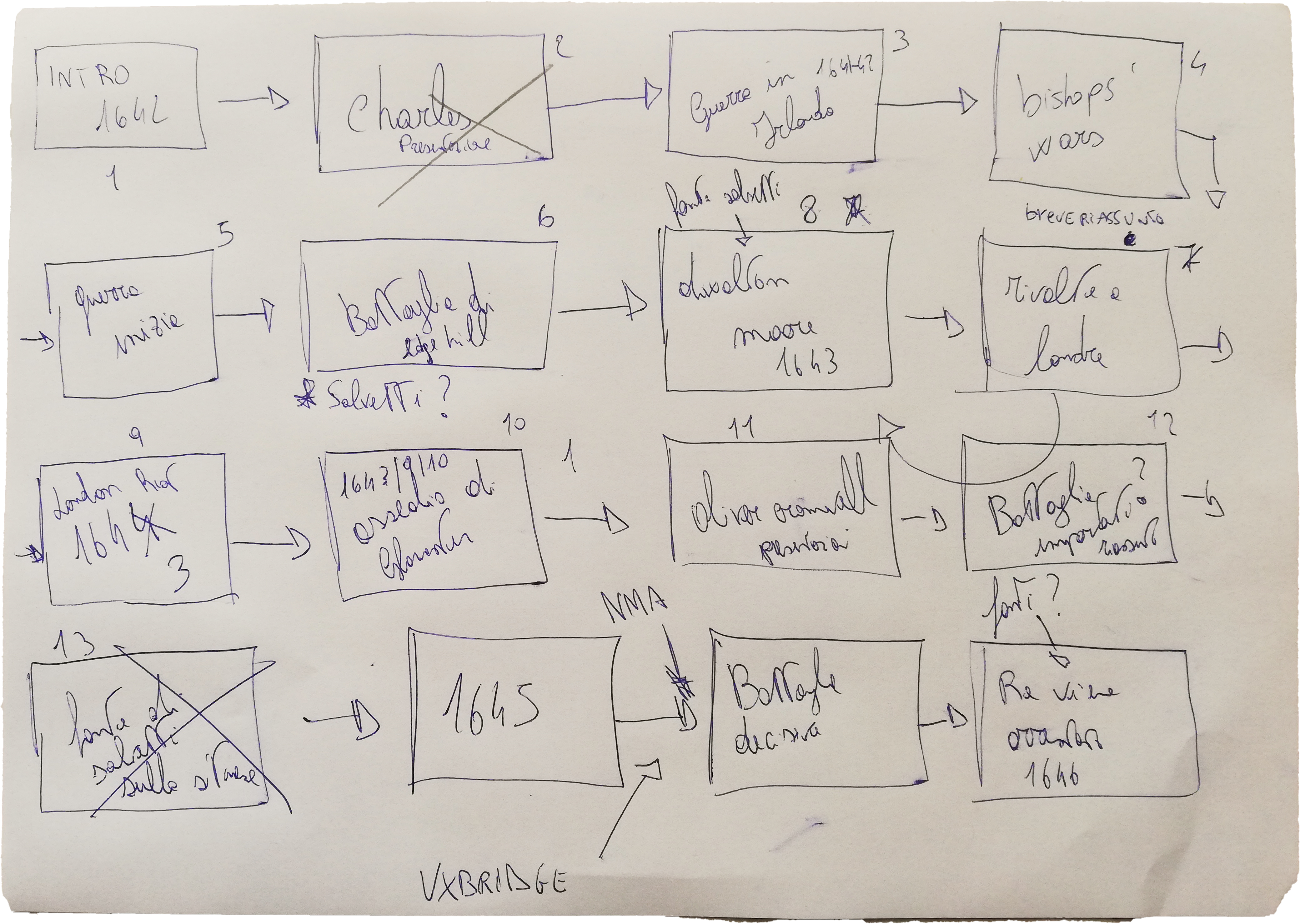

The second step consisted in designing and drawing the main characters of the story. In line with the designated target and with the limitation represented by the fact that only myself was animating, it was decided to create simple characters, very caricatured, who could then quickly associate the face of known historical figures thanks to the exaggeration of some distinctive traits. For example the case of Charles I, designed by emphasising the characteristic moustache and long hair, an image that has been passed down to us in some of the most famous paintings (fig. 2)[4]

Figure 2. Charles I Stuart's comparison.

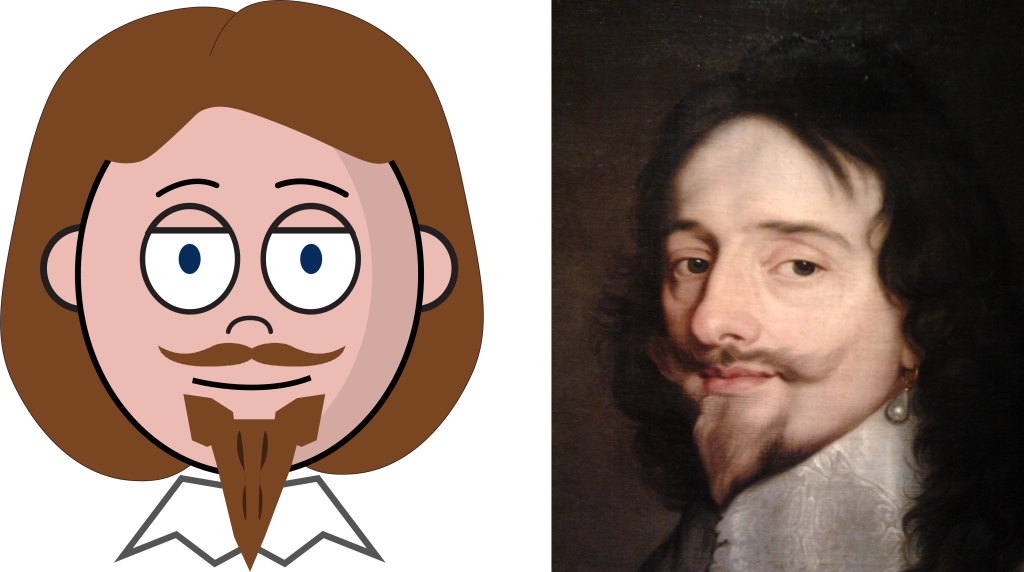

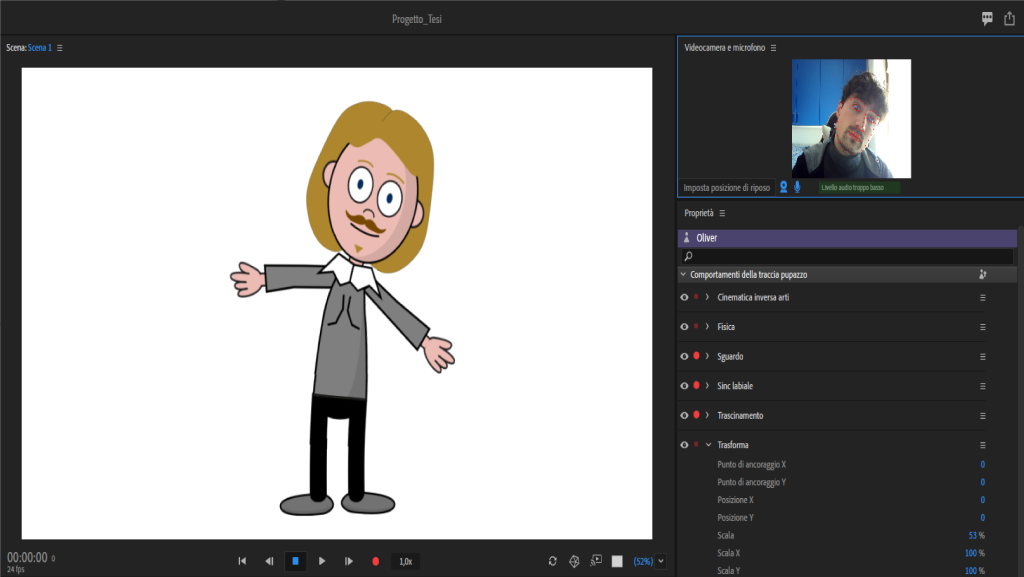

The drawings were made with the help of two software packages: Adobe Illustrator and Adobe Photoshop. Each character can be classified as a vector drawing (a set of gemoetric primitives on various levels) to which colours and shades have been added, giving us the idea of objects and/or body parts. The motivation behind this choice is twofold: firstly, the creation of a character allowed a new subject to be generated with just a few small changes, for example as with Oliver Cromwell (fig.3). Secondly, the simplicity of these designs not only makes them easy to animate, as the levels of which they are composed by can be individually articulated, but they can also be produced by people who are not familiar with drawing, thus creating products with a considerable visual impact. Lastly, it should be remembered that vector graphics are not composed of a grid of pixels. Thus, images do not de-grain when enlarged, as is the case with common raster graphics[5]. This allowed greater flexibility in the creation phase, especially with backgrounds.

Figure 3. Charles I and Oliver Cromwell. By changing the colour of his hair and the shape of his moustache and beard, the model of Charles becomes a new character.

Once all the necessary models had been created, we proceeded to create and search for a set of backgrounds that could match the style of the characters. Due to the complexity of some of the backgrounds, libraries of images were purchased which were suitable for narration, while the simpler backgrounds were constructed using the same technique as the main characters in the video. In order to save time and money in the creation of the backgrounds, some images were reused with simple tricks of perspective and zoom (Fig. 4-5).

Figure 4-5. The two frames shown here belong to two different scenes, but notice that they are the same background, which in figure 5 has been zoomed in order to create a new one, adding some clouds in the background and altering the colours.

Having drawn all the necessary components, I proceeded with the most complicated phase of the video's realisation, the animations. These can be divided into two macro-categories: characters and transitions, such as Salvetti's arm and the maps.

The first ones were created with the help of Adobe Character Animator software, which allows you to manage the individual layers of each vector image in order to create points of articulation and areas designated to the face components. This allows us to make the body of one of our protagonists completely jointed with just a few clicks, making him able to walk and wave with his hand.

The real power of the software is shown by the possibility of animating the face directly by tracing it from a real face with the help of a digital camera and some motion tracking points. As can be seen in Fig. 6, the software draws a tracking mask on the subject's face, then returns individual movements, such as lip and eye movements, to the drawing. The more levels contained in a character, the more fluid and realistic the face animations will be. In our case, this feature allowed us not only to move the lips and eyes convincingly, but also to capture certain facial expressions such as the movement of the eyelids and eyebrows.

Figure 6. Adobe Character Animator's motion tracking. It is possible to see how tracking points have been applied to the real model, and how the digital model responds to suggested movements.

This made it possible to make the protagonists of our story "alive" and engaging. In the video they manage to transmit emotions such as fear, anger and happiness (fig.7).

It should be noted that for every single scene in the video, all the protagonists in the field were animated, giving each individual its own set of articulatory and facial movements (whether simple or complex). In some cases, even some elements of the background were animated, such as the birds in the distance or the smoke produced by the fire.

In some cases, the same set of animations was reused for two different scenes, just changing the background, the clothes of the on-screen characters or simply mirroring the whole image.

Figure 7. In this scene you can see the different expressions of the characters on stage, including fear, anger and happiness.

The whole animation phase took more than two months to produce about ten minutes of product. Obviously, this did not result in a finished video, but only in a few clips, which required additional hours of work in the editing phase and the inclusion of additional animations during this phase.

The editing phase is a delicate moment in the production, as it gives the final shape to the product. The entire work was managed with the aid of Sony Vegas Pro 17, an editor chosen for its flexibility, capable of breaking the usual approach of editing software (source/destination), configuring itself as a tool that works in real time on different audio/video tracks with heterogeneous files. This suited the needs of the project, having different outputs to combine together (e.g. mp4 videos from Adobe Character Animator, png files for drawn and non-animated images, wav audio files).

The editing performed involves three main macro-phases:

- The creation of frame-by-frame animations and transitional animations necessarily handled during this production stage.

- The actual editing stage, in which the animated scenes already rendered by Adobe Character Animator are ordered, making the necessary cuts to their length.

- the creation of transitions to link different scenes together.

- the audio production and mixing phase, during which the necessary sounds are researched and produced and the voice-over narration is recorded.

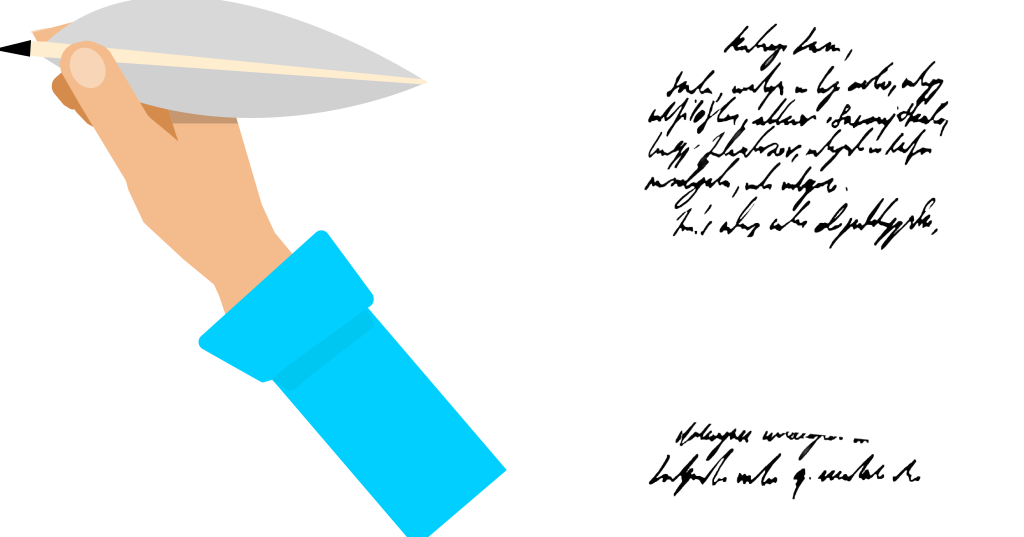

In the first phase, all animations not created with Adobe Character Animator are handled, but rather created frame by frame. To better understand the process, take Salvetti's hand and the animated maps as examples. Both elements were drawn with Adobe Illustrator, trying to create them with a style and colours that blended well with the rest of the animations. In the case of Salvetti’s hand, what is seen on the video is nothing more than the sum of three distinct images, an arm with a pen, the writing and a sheet of paper, moved frame by frame for the entirety of the screen time (fig. 8-9). These were placed in that order, and frame after frame (each second of video is 25 frames), the arm was moved by a few pixels, leaving the paper as a static background, while the writing had a mask applied to it, which made it appear by following the movement of the pen frame by frame.

Figure 8-9. The drawing of the hand and the handwriting. Note that the hand appears in the video at varying angles and zooms in order to simulate movement.

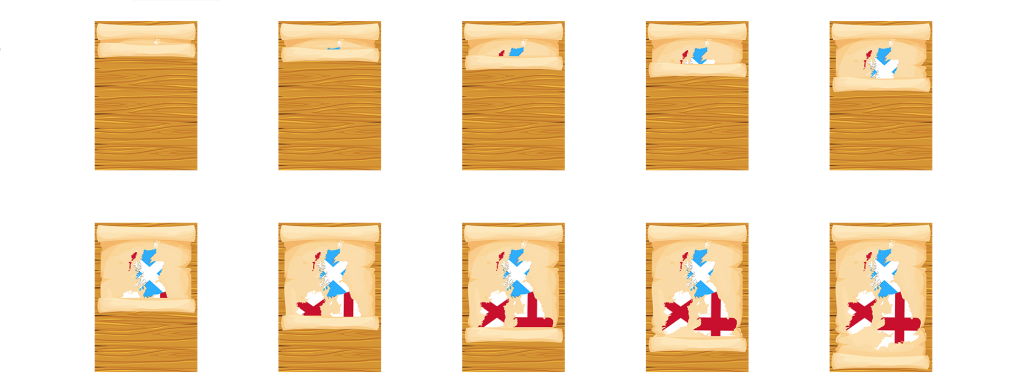

As for the countless maps in the video, they were animated in a very traditional way, by creating a different draw for each frame and quickly putting them in succession during editing. The movements that the camera makes on the map are the result of a digital zoom added during the editing phase, simplifying and considerably reducing the work (fig.10).

Figure 10. The frames that compose the animation of the opening map.

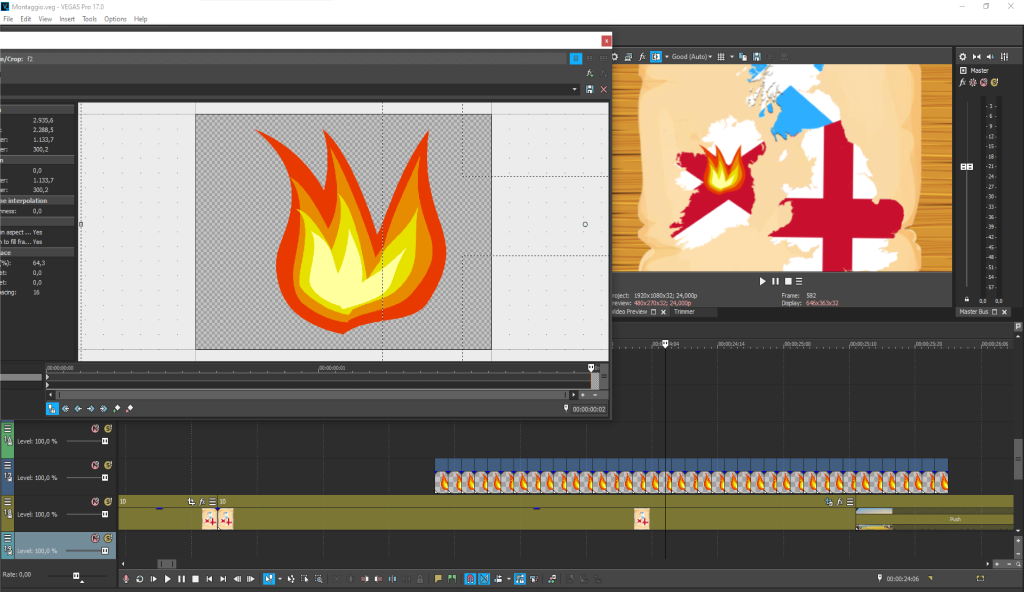

Another example are the simple fires that appear on the already mentioned maps to indicate the beginning of a battle. The animation in question is made up of two frames, consisting in the same drawing simply mirrored and repeated for a set period of time, in order to give the illusion of a burning fire.

Once the animation was obtained (fig.11), it was placed on the video track in question. Since the image has a level of transparency, during the editing phase it was possible to obtain the effect that the fire was present above the map.

Figure 11. On the left you can see the frame of the fire, while below, on the timeline, the alternating repetition of the same so as to give the illusion that the fire is alive.

Once all these animations had been created, the actual editing phase took place, in which all the animations were arranged in such a way as to form a meaningful narrative with a well-defined order.

It was often necessary to repeat cuts and adjustments in the length of the animations because during the audio editing phase there was a need to synchronise an audio that was perhaps too short in duration compared to the video. It should be stressed that, despite its apparent simplicity, this phase defined the real appearance of the final product, generating the actual 'timeline' of the video.

Focusing on the third point of our montage, we dealt with the transitions seen in the video. These were created using the pool of choices that the editing software provides for the user. The choice was not random, but an attempt was made to make each transition as coherent and 'smooth' as possible. For example, when we have Salvetti's hand writing (fig.12), a transition simulating the flip of a page has been used to create a sense of coherence and continuation between two different scenes (fig.13).

Figure 12-13. The two frames clearly show off the 'page' style transition described above.

Once these three phases had been completed, the video was practically complete on the visual level. The audio section had to be included, as there were no ambient sounds or a voiceover narrating the events. The audio editing phase was considerably complicated, as open-source audio libraries containing the necessary environmental sounds are not easy to find. In this case, sounds from the OpenAL[6] software library were used, while others were downloaded from freesound.org[7].

These were modified in the editing phase in order to obtain, as in the battle scenes, a convincing and not too invasive ambient sound, so as to avoid covering the narration. The narration was realised with the help of Audacity, an open-source software with which it is possible to act directly on the recorded material to improve its quality and apply a series of effects or make corrections. In the end, the sum of all these operations results in the final product, which needs to be rendered. In this case an mp4 format with full hd resolution has been chosen, which is well suited in terms of size and quality to uploading onto online streaming platforms.

Sources:

[1] Michael Braddick, God’s Fury, England’s Fire: a new history of English Civil Wars, London, Penguin Global, 2009, pp. 240-478.

[2] Thomas Cauvin, Public History: A textbook for pratice, London, Routledge, 2016, p. 92.

[3] Thomas Cauvin, Public History: A textbook for pratice, pp. 44, 45.

[4] Brain Wood, Adobe Illustrator CC Classroom in a book, San Jose, Adobe Press, 2018, pp. 97, 98.

[5] Ibid., pp 98, 99.

[6] https://www.openal.org/, page accessed on: 22/02/2022.

[7] https://www.freesound.org/, page accessed on: 22/02/2022.

Antonello Mori is Junior Research Fellow in the EURONEWS Project. In 2020, he joined the Internship program coordinated by Dr. Davide Boerio. During this internship he analyzed a series of handwritten newsletters by the Tuscan Resident in London, Amerigo Salvetti, and concerning the so called First English Civil War. This tenure served as a basis for his MA thesis entitled "From the Archival document to the Digital: News of religious, ethnic and political conflicts during the First English Civil War (1642-1646)" and successfully defended at the Digital and Public Humanities Center at the Ca'Foscari University in Venice, under the supervision of the Professor Stefano Dall'Aglio. The project is also part of The Salvetti Project, a collaborative initiative between EURONEWS and Professor Stefano Villani at the University of Maryland. He is currently working on a PhD proposal and he is involved in several digital & public projects.