by Brendan Dooley

When Giulio Gotti writes from Genoa to his brother Raffaello Gotti in Volterra in August 1598, he expresses many of his ideas in code, which is deciphered at destination for the convenience of the recipient. The practice was common wherever sensitive information was being transmitted, for instance regarding war, diplomacy, state secrets, and the like.

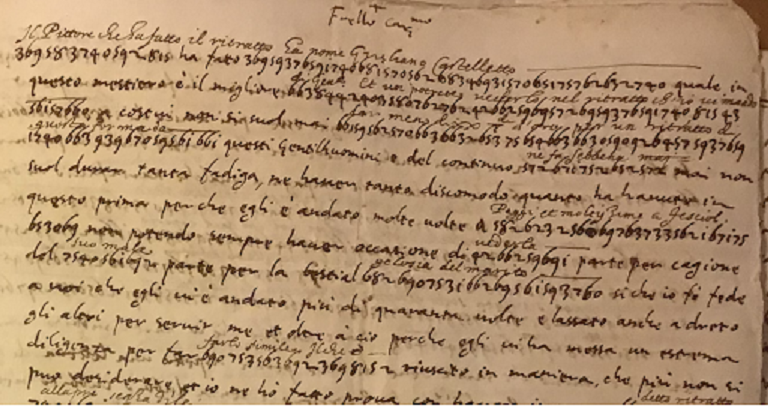

This time the unlikely topic is painting. Thus writes Gotti:

“(in code) The painter who made the portrait is called Giuliano Castellazzo, who is the best in Genoa in this profession, and you will be able to see him in the portrait I send you; he usually gets no less than 20 gold scudi for a portrait in this format from these Gentlemen (of Genoa).”

Mediceo del Principato, vol. 2845 facs 2, n. p. from Giulio Gotti, Letter 8 aug 1598. sent by Giulio Gotti from Genoa to his brother Raffaello Gotti in Volterra

Does this artist require his identity and commissions to be protected from prying eyes?

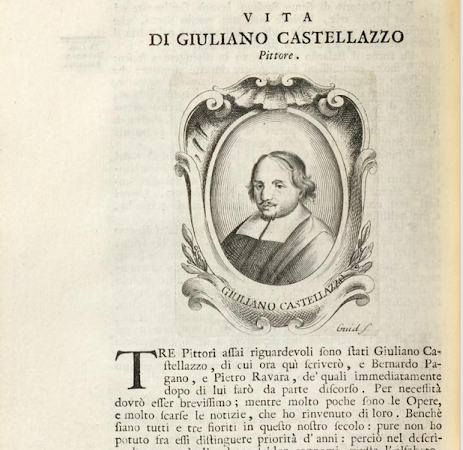

According to Rafaele Soprani’s 1674 history of Genoese art, the artist in question was “very eminent”, indeed, he was “especially loved by the Genoese nobility, who apart from admiring his spiritedness and the pretty little works, appreciated his good looks, affability and nice manners.”

What Soprani fails to mention is that during Castelazzo’s lifetime, indeed, 6 years after the letter we are explaining, Peter Paul Rubens came to Genoa and (according the relevant historiography) initiated the Genoese baroque!

Rubens, Marchesa Brigida Spinola-Doria, Washington, National Gallery

Regarding Castellazzo, apart from a few portraits in private homes, where the artist's work tended to get mixed up with “so many by unknown artists,” the seventeenth-century historian was unable “to find any painting of his to talk about here…..”

Such was the situation in the seventeenth century; and the search for Castellazzo’s works still continues!

However, there may be a coda to our story. What if the reference to the painter was itself a kind of dog whistle? And suppose the entire paragraph about painting and patronage was in a kind of cypher, somewhat like the one we studied in the Featured Post entitled “My Poor Wife is the Duke of Savoy”? We will update when we find the answer!

FURTHER READING

Raffaele Soprani, Le vite de pittori scoltori, et architetti genovesi, Genoa: Giuseppe Bottaro, e Gio. Battista Tiboldi compagni, 1674

Lorne Campbell, Renaissance Portraits: European Portrait-Painting in the 14th, 15th and 16th Centuries, Yale University Press, 1990

Diane Owen Hughes, “Representing the Family: Portraits and Purposes in Early Modern Italy,” Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 17, No. 1 (1986): 7-38

Bernardo Strozzi, Genova 1581-82, Venezia 1644, ed. Giuliana Algeri, Milano: Electa, 1995