By Brendan Dooley

The date is Turin, 20 July 1589. To an unsuspecting reader the letter would seem to be referring to everyday private domestic matters: wife, children, rental incomes, a nephew, the local priest, a doctor, etc.

The writer, Vanni Bardelli, is a correspondent of the Florentine Grand Duke and court, writing from the duchy of Savoy, this time, apparently, to a relative, referred to in the address as “My dearest Alessandra Bardelli,” to whom the letter is to be forwarded by way of another grand ducal correspondent, Lorenzo Guicciardini, in Florence.

We read:

"This morning Annibale’s nephew headed out in a hurry to go see my poor wife, and stay with her a while, which pleases me, and I certainly think my nephew’s presence is necessary, indeed that is what Annibale told him, especially since I know the parish priest keeps shouting that my rents have doubled, almost making fun of my poor wife because my sons, so desired and so anticipated, don’t show up anywhere although I am told they will soon appear, and meanwhile I know my workers are leaving my poor wife and the Com.o every day because of these sons, so I am very afraid for Faustina."

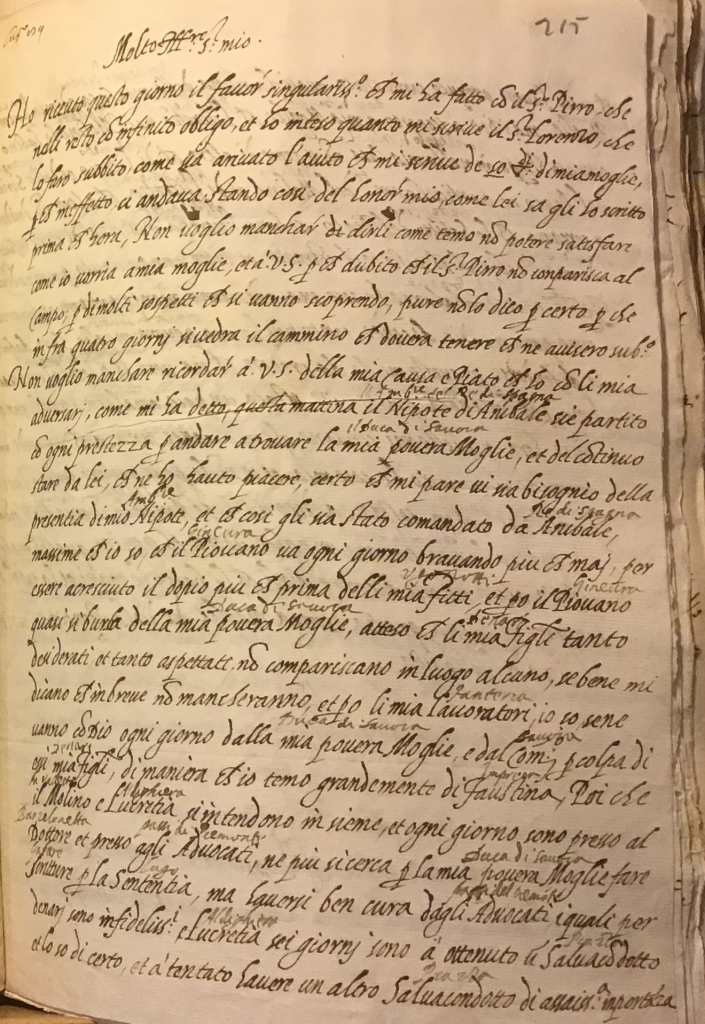

"Questa mattina il nipote di Annibale si è partito con ogni prestezza per andare a trovare mia povera moglie, et del continuo stare da lei, che ne ho hauto piacere,certo che mi pare che ve sia bisognio della presentia di mio nipote, et che così gli sia stato comandato da Annibale, massime che io so che il piovano va ogni giorno bravando più che mai, per essere acresciuto del doppio più che prima delli mia fitti, et però il piovano quasi si burla de la mia povera moglie, atteso che li mia figli tanto desiderati et tanto aspettati non compariscono in luogo alcuno, se bene mi dicano che in breve non mancheranno, et però le mia lavoratori io so che se ne vanno con Dio ogni giorno da mia povera moglie e dal Com.o , per colpa di essi mia figli, di maniera che temo grandemente di Faustina."

MdP vol. 2962, fol. 215

On arrival in Florence, however, the letter has been annotated by someone in possession of a key to the actual meanings of certain expressions, which are far from what they seem.

For instance, over the expression “my poor wife” we find scribbled in, “the duke of Savoy.”. Over “mio nipote” we find “Ambassador,” and so forth, as follows:

In the end, making the suggested substitutions, the text now seems to take us far away from the original domestic scene:

“This morning the Spanish ambassador headed out in a hurry to go see the duke of Savoy, and stay with [him] a while, which pleases me, and I certainly think the ambassador’s presence is necessary, indeed that is what the king told him, especially since I know Geneva keeps shouting that the Huguenots have doubled, almost making fun of the Duke of Savoy because the money, so desired and so anticipated, doesn’t show up anywhere although I am told it will do soon, meanwhile I know the soldiers are leaving the Duke of Savoy and Savoy every day because of this money, so I am very afraid for the enterprise”

The context is important. Charles Emmanuel I is the Duke of Savoy at the time, ambitious to grab more land and turn his duchy into a kingdom. In 1588 he invaded the marquisate of Saluzzo, a protectorate of France, initiating a war with French King Henry III, which is still going on at the time of this letter. He dreams of taking over Geneva, a notorious refuge of French Huguenots, in the name of Catholic Orthodoxy. All he needs, he thinks, is more help from Spanish King Philip II; but Philip has his hands full at the moment, in the aftermath of the futile attempt on England by the Spanish Armada the previous year at a colossal cost in money and men.

We are accustomed to seeing codes in other forms (and we will soon be posting about those too!)--mostly formed by series of otherwise illegible numbers. But what is going on here? Dissimulation in act and speech was a major discussion topic among the learned at the time (Tutino 2014). We are also in the age of the great allegorical poem of Torquato Tasso, Gerusalemme liberata, Jerusalem Delivered, drawing past and present together in a brilliant evocation of heroism, hedonism and hubris set during the first Crusade.

To be precise, the letter was not actually aimed at the Alessandra named in the address, since the greeting reads: “Molto Illustre Signor Mio” very likely, Lorenzo Guicciardini, at least in the first instance. Others too? Maybe we are on the right track in supposing the audience is expected to be the wider grand ducal court environment, notoriously playful and populated by members of both sexes with various degrees of knowledge about the minutiae of communications technology at the highest diplomatic levels, but plenty of interest in the news.

FURTHER READING

Pierpaolo Merlin, Claudio Rosso and Geoffrey W. Symcox, Il Piemonte sabaudo. Stato e territori in età moderna, Storia d'Italia. Vol. 8/1 UTET, 1994

Martha D. Pollak, Turin, 1564-1680: Urban Design, Military Culture, and the Creation of the Absolutist Capital, University of Chicago, 1991

Stefania Tutino, Shadows Of Doubt, Oxford University Press, 2014