By Andrea di Carlo and Brendan Dooley

It was a busy week in Venice. According to the newsletter of 7 March 1592, celebrations were being held here in honor of the newly elected pope; meanwhile, a Veronese person was being executed for desecration of a sacred object; also, a major sailing vessel with its contents worth 90,000 ducats was saved from the Uskok pirates.

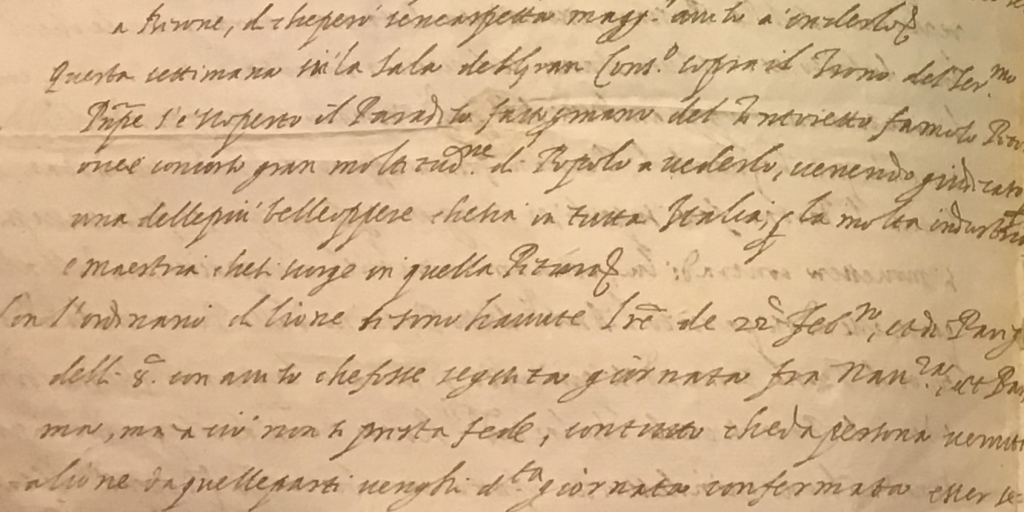

What catches our eye? How about this: “This week in the Hall of the Grand Council above the throne of the Most Serene Prince was revealed the “Paradise” done by the hand of the famous painter Tintoretto, and there came a great crowd of people to see this, which was judged to be one of the most beautiful works in all of Italy considering the mastery demonstrated in that painting.”

MdP 3086 383v 7 March 1592

Direct references to major artworks form a small but consistent undercurrent in all newsletter research, as the art historian J. A. F. Orbaan recognized long ago before much was known about the genre or the network (1920). Jacopo Robusti, known as Tintoretto (1518-94), would have been nearing the end of his life at the time of this news and this work (completed with the help of assistants) which probably depicted the celestial place where he was hoping to end up sooner or later. But before we go much into the significance of this particular moment in the artistic--and political--life of the Republic (and of Tintoretto), let’s take a look at the painting in question:

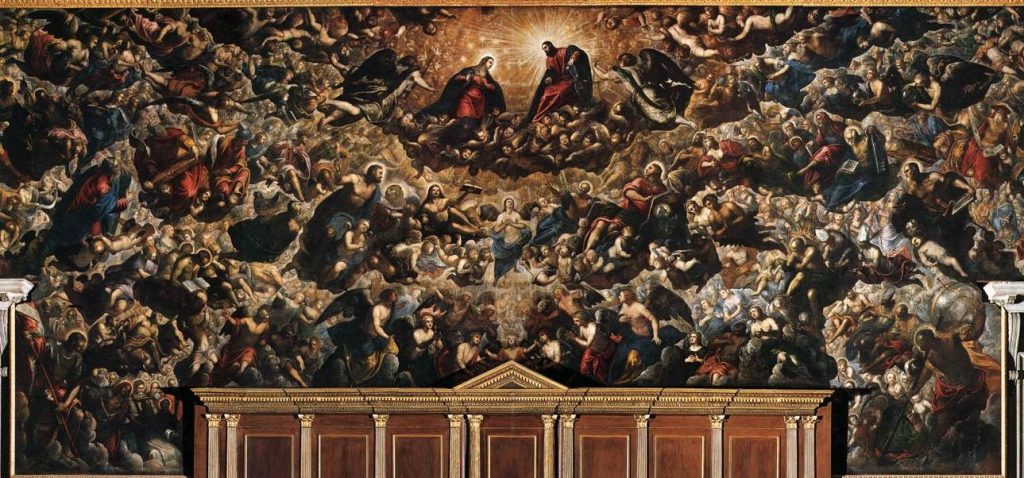

(images from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Il_Paradiso#/media/File:(Venice)_Jacopo_Tintoretto_-_Gloria_del_Paradiso_-_Sala_del_Maggior_Consiglio.jpg )

As is the custom in Venice, in contrast to other places around Italy, we have here a painting on canvas rather than a fresco. Indeed, this work in particular, at 22 feet in length is, according to the Save Venice Fund website, “thought to be the largest painting on canvas in the world.” [https://www.savevenice.org/project/jacopo-tintoretto-paradise]

The painting portrays the reunion in Paradise between Christ and the Virgin Mary. Christ can be clearly seen thanks to light upon His head. Amongst the many religious figures of note are St Mark the evangelist, patron saint of Venice (depicted on the left-hand side of the painting, with the symbolic lion next to him):

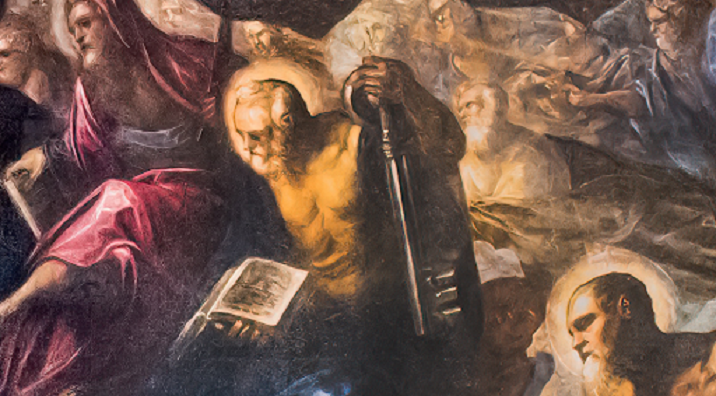

Beside Christ, the Virgin Mary and St Mark, other figures of Roman Catholic theology can be spotted. On the right-hand side, relatively far from the center of the painting, one can see St. Peter, holding the key to Heaven (below). What is the image in the book he holds?

To the left of St. Peter, St Paul can be seen, holding a book with a sword referring to epistles and martyrdom.

Stepping back again to take it all in, we note that this splendid painting stands above the throne of the Doge, the ruler of Venice. So the meaning of the painting may be equally secular and religious. Venice has a special status within the complicated political landscape of sixteenth-century Italy. In the aftermath of the Reformation and the Tridentine Council, the Republic had established its own harsh way of dealing with religious nonconformity. But relations between Venice and the Papacy were somewhat fraught. Certainly the widespread commercial and financial activity even in non-Catholic lands seemed to thrive best without ecclesiastical interference. (Santarelli 2007: 73-105, Pittalis 2017: 59).

The position of the painting invites reflection about the relation between the Doge, the Church and God. Is there a subtle signal here that secular authority should not be undermined by papal directives? Divine grace seems to flow down upon the doge and senate, with no mediation, as though rulership is by divine right. Moreover, the main political theory of the time, Reason of State (ragion di stato), suggested a clear division between Church and state. Venice was undoubtedly Catholic but, at the same time, religious allegiances could not prevent it from trading or building long-standing commercial bonds wherever it wished or even trying ecclesiastics in civil courts; thus, one meaning of the painting seems to point to Venice’s ambivalent attitude: Catholic in matters of faith, secular in everything else. Consider the figure of St Mark: not only an evangelist but also, with his lion, a symbol of Venice. So in embodying the religious and the secular, do the two images represent the acceptance of religious dogma and, at the same time, the needs of commerce?

Just in this period tensions were building between Venice and the Church. Eventually Servite friar Paolo Sarpi, author of a famous history of the Council of Trent, would take the side of Venice. Scholars have asked, were his expressions genuine or were they instead, like those of most politicians at that time, a form of extreme caution? Even in his political beliefs, he was shaped by the ambivalent relations between Rome and Venice, trying to be vocal and prudent at the same time (Wootton 1983, 2002: 68). But more on that in another post!

In any case, the crowd in our newsletter saw before them a beautiful image as well as a very important and complex locus of discussion on politics and religion regarding where Venice stood in the contrast between reason of state and reason of Church. No wonder they were excited!

Further Reading:

Pittalis, Gian Nicola (2017) L’Inquisizione a Venezia. Castelfranco Veneto: Biblioteca dei Leoni.

Santarelli, Daniele (2007) Eresia, Riforma e Inquisizione nella Venezia del Cinquecento. Studi Storici Luigi Simeoni: 73-105.

Wootton, David (1983, 2002) Paolo Sarpi: Between Renaissance and Enlightenment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Orbaan, J. A. F. (1920) Documenti sul barocco in Roma (Rome: Società alla Biblioteca Vallicelliana.

Nichols, Tom (2015) Tintoretto: Tradition and Identity 2nd ed. London: Reaktion Books.