By Brendan Dooley

Trouble in Rome! The Rome newsletter of 23 October 1582 informs:

“The Congregation responsible for the reform and intercalation of the year has heard from Naples about a serious error in the printed version, such that the pope having heard about this has initiated discussions, and nobody knows where this is going to lead.”

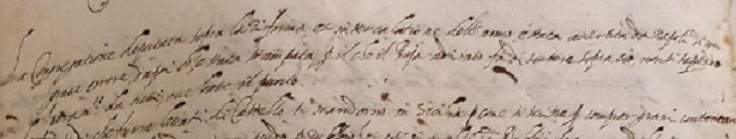

Florence, Archivio di Stato, Mediceo del Principato (MdP) fol 334v, Rome, 23 oct 1582

[La Congregazione deputata sopra la riforma, et intercalatione dell’anno, è stata avertita da Napoli di un grave errore dapoi ch’è stata stampata, per il che il papa advisato fa discutere sopra ciò, non si sapendo veramente da tutti, ove batte il punto.]

Apparently, information coming out about the new calendar reform by Pope Gregory XIII is becoming garbled in transmission. The news comes by way of Naples, that a “serious error” has been noted in the last decree. What has happened? Time will tell….

Almost to remind us that time was indeed of the essence, another piece of news on the same page, tells of a massive gold watch having been gifted to the pope:

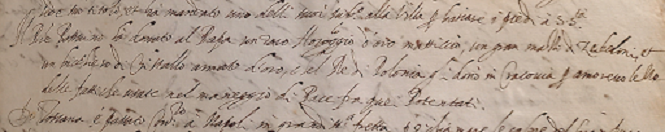

[Il Padre Possevino ha donato al Papa un raro Horologgio d’oro massiccio, un gran masso di zebellini, e un bicchiero di Cristallo armato d’oro, chel Re di Polonia gli donò in Cracovia per amorevolezza delle fattiche usate nel maneggio di Pace fra quei Potentati.]

Let’s take a step back.

Among the major accomplishments of international collaboration in applied astronomy on a colossal scale was the calendar reform that gave us the calendar we use now. Called “Gregorian” for the pope, Gregory XIII, under whose aegis the last stages of the long-planned and long-awaited reform took place, the initiative succeeded in removing ten excess days from the older Julian calendar, which had been accumulating due to discrepancies between the revolutions of the heavens and the revolutions of human time without sufficient regularity of correction. Equinoxes, solstices, and the rest, had been moving subtly but steadily across the months, with nothing in the way to stop them. Worst of all, the annual computus, defined as the day on which Easter must be celebrated according to the traditional criteria stipulating the first full moon after the vernal equinox, was already drifting back into early March. Something had to be done, and the community of astronomers including Egnazio Danti and Christopher Clavius, using meridian lines in Bologna and Florence, drawn on the floors of the churches of San Petronio and Santa Maria Novella, respectively, produced improved calculations of the length of the year.

Of course, decrees are one thing; obedience is another. Even in regions not far from Rome, the news takes time to sink in, and even longer to result in action. The pope however is patient and grants a little more time to those concerned:

“Another printed edict has come out in which the pope orders that those who have not begun to observe the intercalation of the year in the month of October must begin to do so on the 10th of February 1583, which will be called the 21st.”

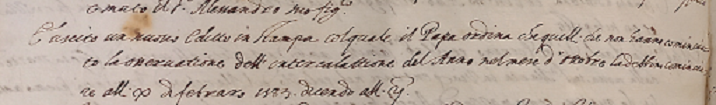

fol 345v, Rome, 13 nov 1582

[E’ uscito un nuovo Editto in stampa col quale il Papa ordina che quelli che non hanno cominciato la osservatione dell’intercalattione del Anno nel mese d’Ottobre la debbino cominciare alli 10 di febraro 1583, dicendo alli 21.]

Meanwhile, newsletter writers try their best to indicate which style of dating they are adopting at any given time, as we find in this excerpt regarding news from Vienna:

“Some write from Vienna that the Emperor was leaving for Possonio [Preßburg] on the 24th of March, new style, from which, having made the proposals His Imperial Majesty intends to make in that Diet, would return to Vienna…”

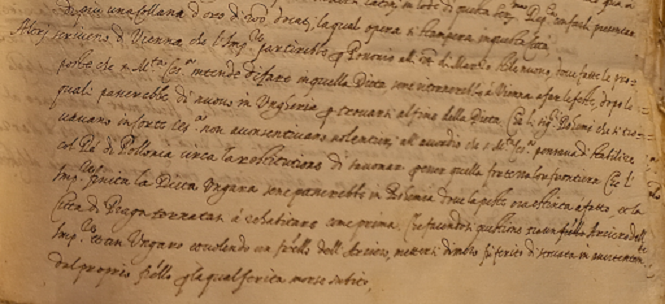

fol. 438, Venetia, 8 April 1583

[“Alcuni scriveno di Vienna che l’Imperatore partirebbe per Possonio [Preßburg] alli 24 di Marzo stile novo, dove fatte le proposte che Sua Maestà Cesarea intende di far in quella Dieta, sene ritornerebbe a Vienna…”]

To be sure, adoption of the new calendar was by no means immediate or uniform. Indeed, news readers (and writers) had to remember not only that England and Italy were generally many days apart until well into the eighteenth century, but that January 22 in, say, the Duchy of Prussia, might be 11 January in, say, the Duchy of Westphalia, until 1610, when Prussia changed, with the Principality of Minden remaining behind until 1688.

FURTHER READING

John Heilbron, The Sun in the Church: Cathedrals as Solar Observatories (Cambridge, MA: 1999)

George Coyne, M.A. Hoskin and O. Pedersen, eds. Gregorian Reform of the Calendar (Rome: 1983).